Communities of Color in Crisis: Examining Racial Disparities in Student Loan Debt and Borrower Outcomes

By Kat Welbeck | January 8, 2020

The student debt crisis touches nearly 45 million borrowers across the nation, but communities of color, in particular, are shouldering the most severe consequences associated with this debt. African American and Latino students are more likely to take out loans than their white peers and face additional hurdles in repayment. For example, despite the promise of programs like income-driven repayment (IDR) that should make it near impossible to default on a federal student loan, borrowers of color are defaulting on their loans at disproportionately high rates.

As reports of widespread servicing breakdowns leading to significant borrower harm continue to emerge, it is critical that we examine the disparity in loan performance between borrowers of color in comparison to their white peers, the role of student loan servicers in exacerbating these outcomes, and the federal inaction that allows potential discrimination by student loan companies to go unchecked.

The Equal Credit Opportunity Act (ECOA), a federal fair lending law, was created to prevent discrimination and promote more equitable consumer finance markets. These protections exist to prevent instances where borrowers receive varying access to credit transactions. In mortgage servicing, for example, it is illegal for servicers to impose hurdles that prevent homeowners of color from obtaining affordable mortgage payments, when compared to similarly-situated white homeowners. Likewise, in the student loan market, varied outcomes in benefiting from IDR should raise red flags about potential fair lending risks and spur regulators and law enforcement officials to act to determine if there are violations.

The Disparate Burden of Student Debt

The racial wealth divide contributes to greater debt burdens for communities of color. African American and Latino students use student loans to finance higher education at greater rates than their white peers.

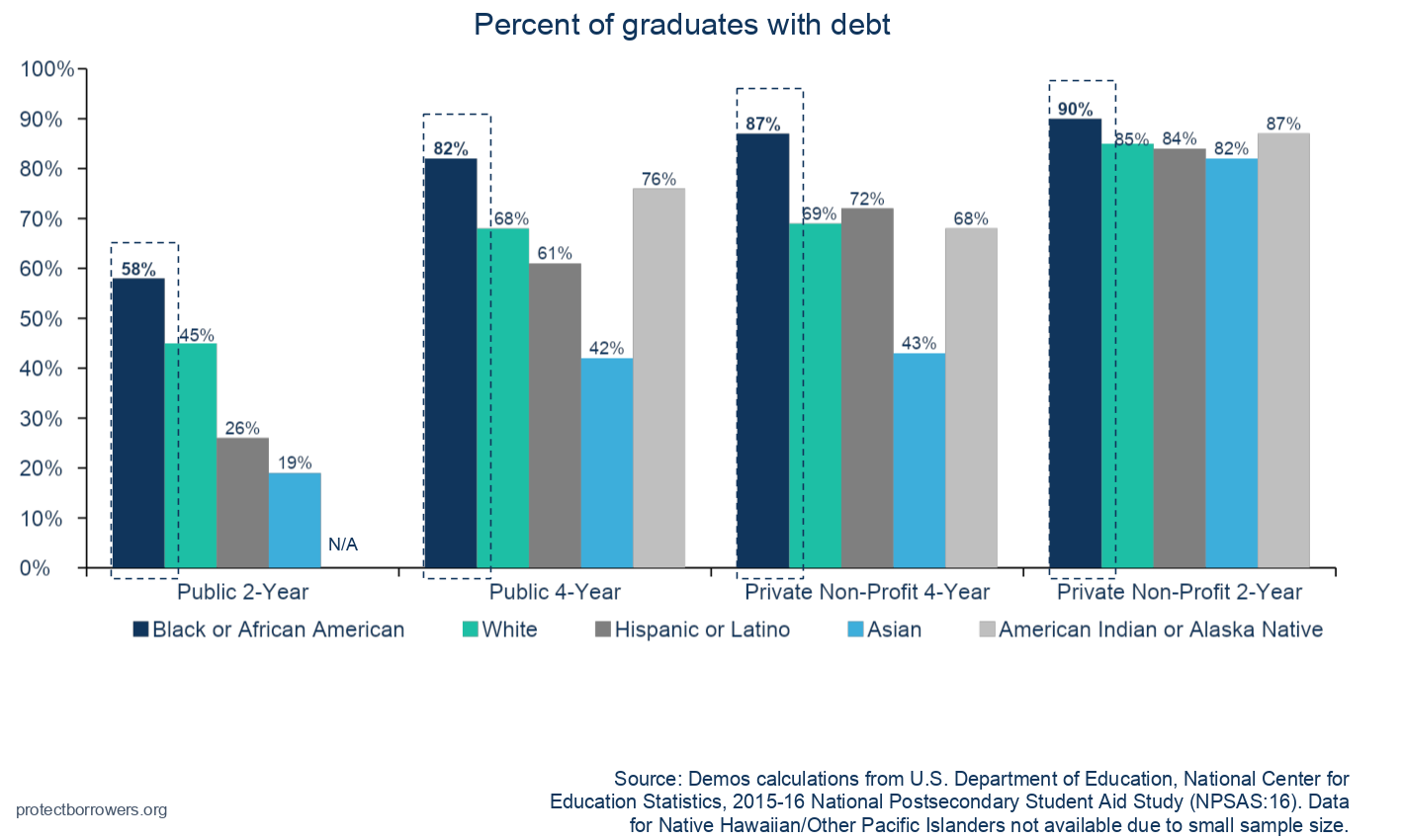

- More than 90 percent of African American and 72 percent of Latino students take out loans to attend college in comparison to 66 percent of white students, according to a 2016 analysis from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB).

- African American borrowers take on more debt for higher education, regardless of school sector, including: public two-year and four-year colleges, private colleges, and for-profit institutions.

- Data from the Pew Research Center found the average white household has 13 times the wealth of the average African American household and 10 times the wealth of the average Latino household. As a result, African American and Latino borrowers must take on more debt to attend college.

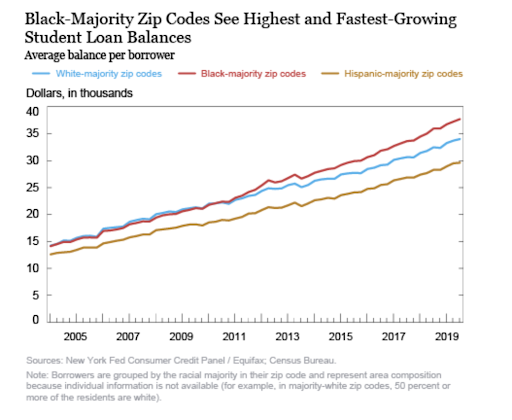

- The highest and fastest-growing student loan balances are in majority-black communities, with an average balance of $38,000, approximately $5,000 greater than the national average, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

- Further, the typical white borrower pays down almost 95 percent of his or her loans in the 20 years after starting college, whereas his or her black peers will still owe 95 percent of their original balance after the same period.

The borrowing gap in student loans between white borrowers and borrowers of color is seemingly intergenerational in nature. As previously discussed, borrowers of color, particularly African American borrowers, have less household wealth and take on more loans to pay for higher education. These borrowers then leave school with more debt, cutting into opportunities for wealth creation. When their children attend college, the cycle often repeats.

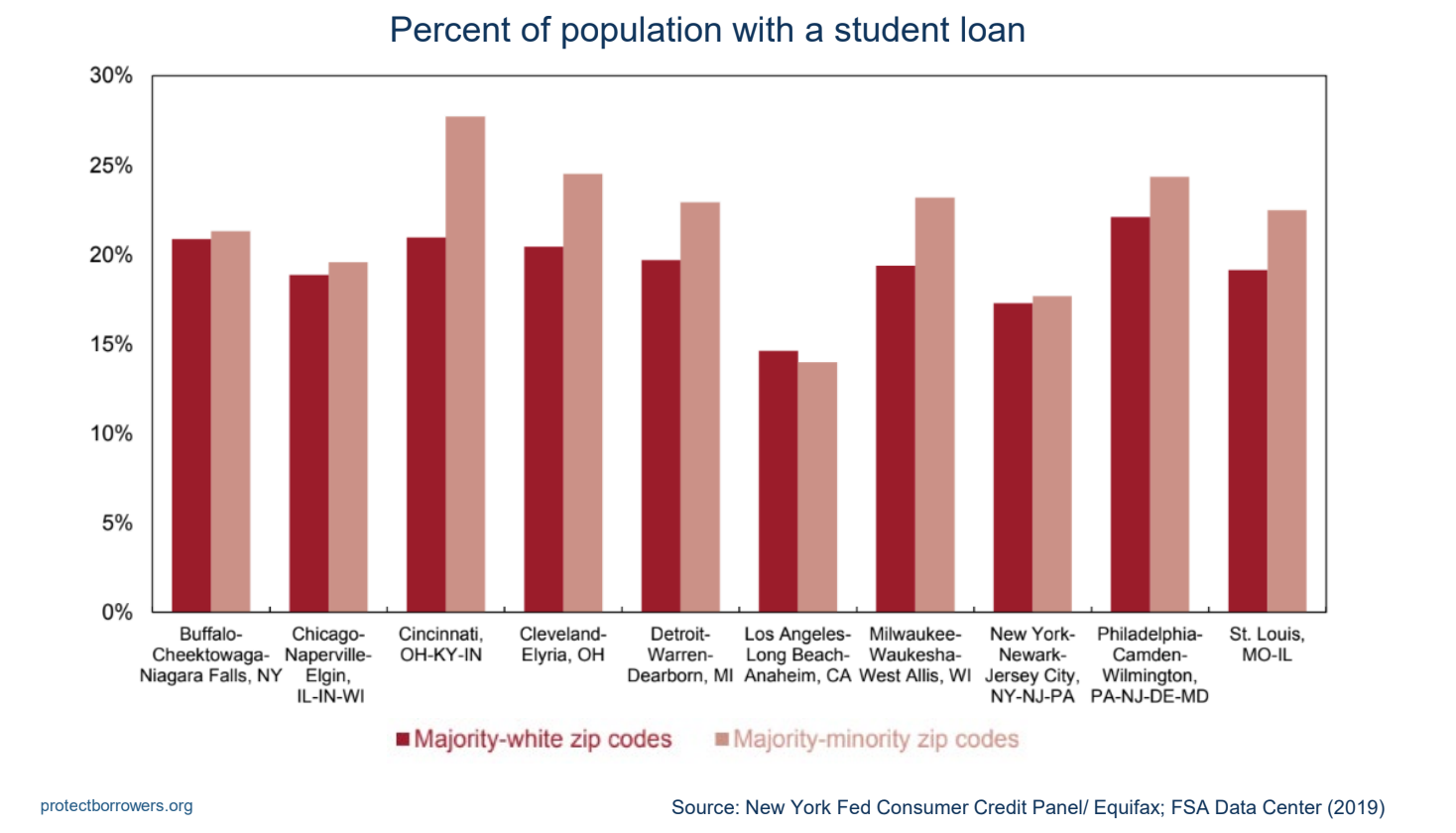

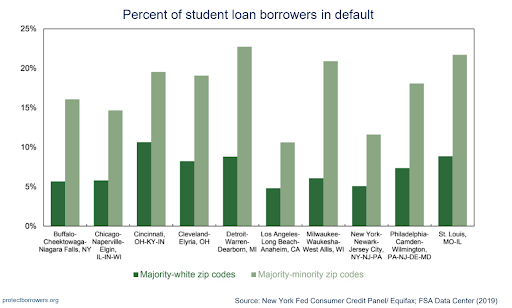

This cycle is evident in a recent report from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York highlighting significant gaps in debt burdens between majority-white and majority-minority zip codes in ten of the nation’s most segregated cities.

In nine of the ten cities identified, majority-minority zip codes had larger percentages of their populations with student loan debt.

Black and Latino Borrowers Experience Student Loan Default at Higher Rates than their White Peers

Existing data also provides evidence that borrowers and communities of color are disproportionately affected by student loan defaults.

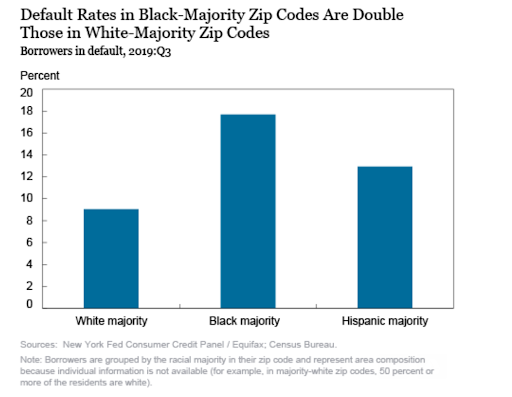

- The Federal Reserve Bank of New York’s data on default rates in majority-black and majority-white zip codes found that the default rate is 17.7 percent in black-majority zip codes, approximately 13 percent in Latino-majority zip codes, and 9 percent in white-majority zip codes.

- Majority-black zip codes have default rates nearly double those in white-majority zip codes, and Latino-majority zip codes have default rates nearly 4 percent higher than those in predominantly white areas.

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York also examined default rates in ten of the most segregated metropolitan areas in the country. The city-level data, in conjunction with the national data, provides one of the most comprehensive government explorations into how default is unfolding in communities across the country. In both national and city-level data, default rates in majority-minority communities are significantly higher than default rates in predominantly white communities.

In America’s most segregated metropolitan areas, the gap in default rates between some majority-minority areas and majority-white areas are significantly higher than when analyzing the racial gap in default rates at a national level.

Of the 18 New York City neighborhoods that ranked highest for default, 13 also had the highest percentage of black residents, and 6 had the highest percentage of Latino residents in the city. In the Bay Area, neighborhoods with the highest percentage of black and Latino residents had default rates three times higher than neighborhoods with the lowest percentage of black and Latino residents according to research from the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco. Similarly, the Washington Center for Equitable Growth found at both the city and national-level zip codes with higher proportions of African Americans or Latinos have higher delinquency rates. The grim reality of default disparities across the nation calls for a deeper exploration into the causes and action to mitigate such widespread gaps.

Race-Based Gaps in Defaults Call for Examination of Student Loan Servicing Practices

While economic differences between borrowers of color and white borrowers may seemingly explain default disparities, existing data suggests that is not the full story. Columbia University professor Judith Scott-Clayton found that controlling for income accounts for only approximately half of the default gap between black and white borrowers. Additionally, as noted in those findings, “even accounting for differences in degree attainment, college GPA, and post-college income and employment cannot fully explain the black-white difference in default rates, which remain large and statistically significant at 11 percentage points in the most complete model.” According to Scott-Clayton, this discrepancy may in fact be tied to student loan servicers—the companies tasked with collecting loan payments and administering default mitigation programs like income-driven repayment.

Disparities in Income-Driven Repayment Can Be Linked to Higher Delinquency and Default Rates for Borrowers of Color

Federal law provides a series of borrower protections designed to mitigate the financial distress of federal student loans, including near-universal availability of IDR plans. IDR plans are intended to provide access to affordable monthly payments and are available to nearly all federal student loan borrowers. These plans can offer payments as low as zero dollars for the most vulnerable borrowers, and this payment relief can last for years or even decades, provided the borrower documents their eligibility each year through a process called recertification. Servicers are responsible for informing borrowers about the availability of IDR, and also enrolling and recertifying borrowers’ eligibliy for IDR plans.

Access to IDR should make student loan defaults extremely rare, by decreasing the likelihood of default for those who maintain eligibility for payment relief year after year. For example, a 2015 GAO report to Congress found that default rates for borrowers who are not enrolled in IDR are 28 times higher than those enrolled in IDR, with 0.5% of IDR borrowers and 14% of borrowers in standard repayment plans defaulting over the same period. Similarly, a recent report from the CFPB found that borrowers who do not continue to benefit from IDR will struggle; for borrowers who did not recertify their IDR plan on-time after their first year, delinquencies more than tripled, whereas delinquencies improved over time for borrowers who recertified after their first year of IDR.

In addition to mitigating delinquency and default, according to recent research by economics professor Daniel Herbst, borrowers who enroll in IDR plans also repay more of their principal balances and develop stronger credit profiles.

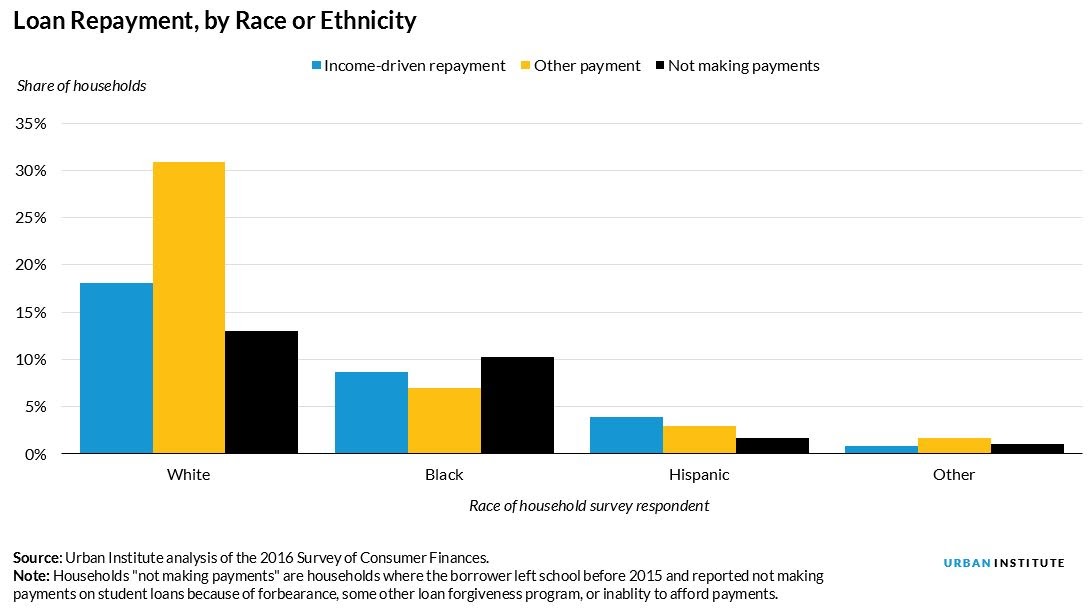

However, evidence on IDR enrollment by black borrowers is mixed.

Some data shows that borrowers of color are accessing IDR at higher rates than their white peers, but failing to benefit from this critical protection. According to a Center for American Progress analysis of 2017 Department of Education data, one-third of black borrowers with a bachelor’s degree who are in repayment use IDR—more than any peer group. However, the same analysis by Ben Miller at Center for American Progress suggests that even when black borrowers manage to enroll in IDR, they may not realize the same economic benefits over the long term as white borrowers and continue to default at extraordinarily high rates—a potential result of disparities in recertification. Other research shows that borrowers of color may be struggling to access IDR in the first place, and therefore fail to benefit from this protection.

Notably, the Urban Institute found that borrowers of color are nearly as likely to not be making any payment as they are to be making IDR payments.

Taken together, this evidence suggests that borrowers of color are needlessly and disproportionately exposed to increased risks of default. Servicing failures can directly affect borrower outcomes, which leads to questions about systemic discrimination in the student loan market and calls for increased oversight and enforcement to protect borrowers.

Federal Action Should Address Civil Rights Issues in the Student Debt Crisis

Regulators have important authorities under existing fair lending laws enacted to ensure that servicing practices are not adversely affecting borrowers of color. ECOA prohibits creditors, such as financial institutions and other lending entities, from discrimination in the extension of credit on the basis of borrower characteristics, such as race, color, religion, national origin, sex or marital status, or age. Historically, ECOA has provided recourse to consumers in instances where creditors engaged in disparate lending practices for certain subsets of borrowers across consumer finance markets.

ECOA bars student loan servicers from discriminatory actions against borrowers, in any part of the credit transaction. Credit transactions are broadly defined under the law to cover “every aspect of an applicant’s dealings with a creditor regarding an application for credit or an existing extension of credit.” For example, when a servicer evaluates a borrower’s request to modify his or her student loan payments, this is considered a credit transaction as the servicer must make a decision regarding the terms of the debt’s repayment. In this respect, ECOA applies to a range of servicing functions, including IDR enrollment and recertification.

Enforcing Existing Federal Fair Lending Laws Could Mitigate Borrower Harm

The CFPB previously made note of potential discrimination risks in student loan servicing when Patrice Ficklin, director of the Bureau’s Office of Fair Lending, stated “we’re looking at disparate outcomes…and we believe there may be some.” Accordingly, in 2017, the agency committed to oversight of fair lending compliance in the student lending market.

However, recent reports show that these authorities are no longer being used to protect borrowers from discrimination. As data continues to highlight the need for additional student loan servicing oversight, particularly with a lens on racial disparities, the CFPB has changed course and is not using its authority to defend vulnerable borrowers of color. That is why, earlier this year, a wide range of civil rights organizations joined the SBPC in advocating for the use of ECOA for oversight in student lending.

Fair lending protections are a critical tool that regulators must use to ensure borrowers are not subject to illegal discrimination. It is imperative that those charged with industry oversight vigorously use all tools and remedies available to root out discrimination in the student loan market—that includes the CFPB, but also state law enforcement officials who are also empowered to police discrimination in the student loan market.

The student debt crisis is both a civil rights and consumer protection issue. Borrowers of color are defaulting at alarming rates and significantly more often than white borrowers. At the same time, protections exist to help all borrowers avoid default and access affordable repayment plans.

Why are borrowers of color not benefitting from these protections at the same rate as their white peers? This is a question that regulators must address by using their authorities to determine servicers’ role in disparate borrower outcomes.

Downstream effects for borrowers of color, such as damage to a borrower’s credit, can negatively impact employment options, access to and cost of credit, and cost of insurance, among other essentials. The severity of negative economic consequences that accompany default demands urgency in action. Pursuing the American Dream through higher education should not have a hand in causing personal economic harm and furthering racial socioeconomic inequality.

###

Kat Welbeck is a Civil Rights Counsel at the Student Borrower Protection Center. She was previously an Outreach & Engagement Specialist in the CFPB’s Office of Public Engagement & Community Liaison. Kat is also the Director of Engagement on the Rising Leaders, Inc. Board of Directors. She holds an A.B. from Princeton University and a J.D. from the University of Pennsylvania Law School.