November 3, 2022 | Dalié Jiménez and Ben Kaufman

Recently, the Student Borrower Protection Center (SBPC) reported that a decades-long student loan industry scheme may have deceived millions of borrowers out of the right to relief through bankruptcy. As the SBPC describes it, the largest creditors in the private student loan market, including Navient and Sallie Mae, misled borrowers for years into believing that tens of billions of dollars of private credit used to finance education could not be discharged in a typical consumer bankruptcy when, in fact, they could. The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) appears to have confirmed in April 2022 that creditors are skirting the law, including by “unlawfully collecting on loans even after a borrower has been through bankruptcy.” An October 2022 CFPB report echoed this finding, and a judge recently issued a temporary injunction blocking Navient from collecting on these dischargeable loans.

However, the extent of fraud present here may run even deeper. In particular, the misrepresentations that lenders made in this scandal concern not just borrowers’ rights in bankruptcy, but also their ability to access certain special tax deductions. That means that in the course of robbing borrowers of their bankruptcy protections, student loan companies may have also routinely made misrepresentations on tax filings and may have driven student loan borrowers to make false statements on tax forms—all to perpetuate the myth that these loans could not be discharged in a typical bankruptcy. It’s long past due for the IRS and the CFPB to get to the bottom of what happened here.

Qualified Education Loans and the Student Loan Interest Deduction

Student loan borrowers are able, with certain limitations, to deduct up to $2,500 in interest each year that they pay on their student loans. This deduction applies both to federal student loans and certain private student loans that meet the definition laid out in the tax code of a “qualified education loan.” In general, this definition encompasses loans that are taken on by a student who is eligible for federal student aid at a program that is eligible for federal loans and grants, and that are used only for “qualified educational expenses” such as tuition, room, and board.

There are a wide variety of loans used for higher education financing that fall outside the definition of a “qualified education loan,” but that lenders nevertheless systematically represented as ones that would remain after a bankruptcy.

This definition of a “qualified education loan” is referenced in the bankruptcy code to determine whether a given private loan used to pay for education expenses receives special treatment in bankruptcy. The SBPC alleges lenders exploited borrowers’ confusion about these rules to steer them away from pursuing or realizing the possibility of bankruptcy discharge. In particular, as the SBPC outlines, there are a wide variety of loans used for higher education financing that fall outside the definition of a “qualified education loan,” but that lenders nevertheless systematically represented as ones that would remain after a bankruptcy (unless the student proved that it would be an “undue hardship” to repay them). The loans underlying these misrepresentations include bar study loans, “direct to consumer” loans disbursed to cover expenses beyond students’ cost of attendance, and “career training” loans to students at unaccredited—and often for-profit—training programs.

Lenders’ Lies May Have Robbed Taxpayers in Addition to Borrowers

In the course of misrepresenting what is and isn’t a “qualified education loan” in the context of bankruptcy, creditors may have also deceived the federal government regarding which loans did and did not qualify for the federal tax deduction for student loan interest paid during the course of each tax year. And that means student loan companies could have effectively taken billions of dollars out of federal and state coffers.

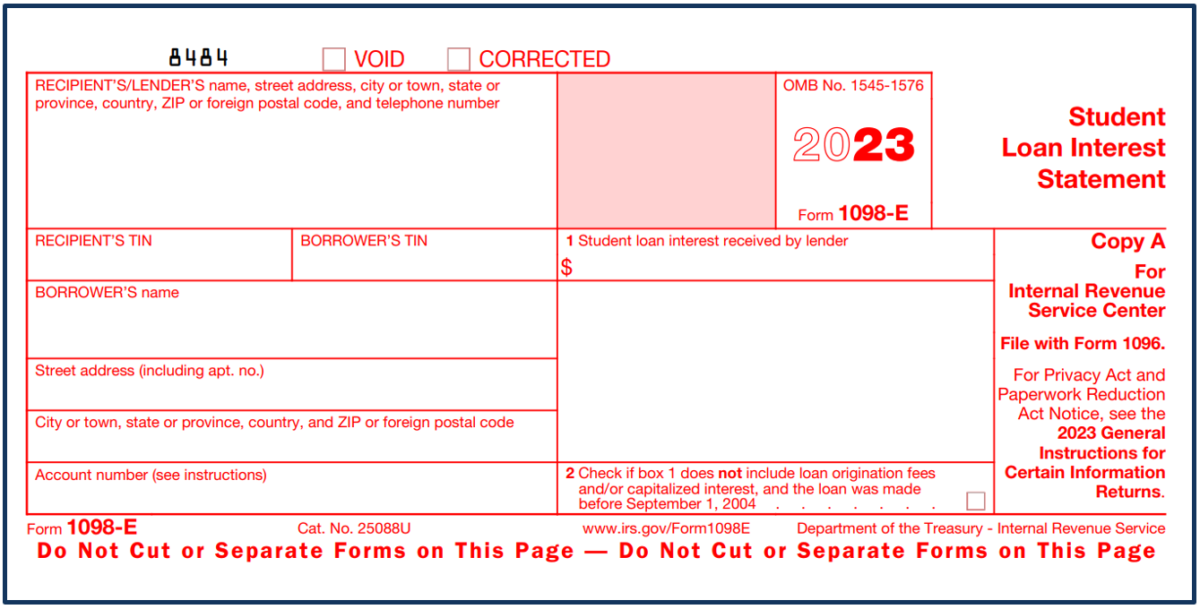

The issue involves how borrowers go about deducting student loan interest on their federal tax returns. Borrowers can claim the deduction for interest payments on eligible student loans using the IRS’s form 1098-E. But this form is not one that borrowers can simply seek out and file on their own; it is one that their lender must send to them with certain portions already filled out, and where the lender’s choice to send the form in the first place is likely to create the impression that the loan is a “qualified education loan” per the definition above.

In particular, form 1098-E itself states, “A person (including a financial institution, a governmental unit, and an educational institution) that receives interest payments of $600 or more during the year on one or more qualified student loans must furnish this statement to you.” (emphasis added). The phrase “qualified student loans” is used here, but elsewhere the IRS states, “A qualified education loan is generally the same as a qualified student loan.”

Glaringly, creditors (or student loan servicers on creditors’ behalf) must also file a copy of this form with the IRS each year for each borrower, indicating that the creditor received “student loan interest” from the borrower. To maintain the scheme to deny bankruptcy rights to borrowers, the largest creditors in the student loan market may have knowingly and improperly filed millions of false tax forms, each containing inaccurate information about the amount of “student loan interest” paid.

The SBPC’s bankruptcy investigation showed that companies like Sallie Mae and Navient were telling borrowers in ads, communications, contracts, and court filings that their loans were qualified education loans even when they weren’t. Either companies followed this fiction through to the natural conclusion that these non-qualified education loans would also (incorrectly) be eligible for the student loan interest deduction by sending borrowers 1098-E forms, or they didn’t.

But the record is damning in either case—if lenders did send borrowers 1098-E forms, they directed borrowers to incorrectly claim the interest deduction so as to keep up the lie that their loans were not dischargeable in bankruptcy. If lenders did not, they clearly understood that the representations they were making elsewhere about loans not being dischargeable were incorrect.

Notably, if lenders did send borrowers 1098-E forms, and if borrowers did go on to take the student loan interest deduction as their creditors may have led them to believe they were eligible to do, the losses for taxpayers could run into the billions of dollars.[1] In other words, huge sums of money could be involved here—all in the service of lenders’ efforts to keep borrowers from pursuing bankruptcy as they were entitled to under the law.

It’s clear that the IRS needs to get to the bottom of what happened here. And if the CFPB is looking into these practices, Dodd-Frank explicitly mandates that the Bureau turn over any “information identifying possible tax law noncompliance” to the IRS. There may be even more fraud to discover, and there is certainly a need for someone to finally be held accountable—families have been harmed enough by this scheme.

###

Dalié Jiménez is a professor at UC Irvine School of Law and co-founder of the Student Loan Law Initiative. Professor Jiménez’s scholarly work focuses on contracts, bankruptcy, consumer financial distress, the regulation of financial products and its intersection with consumer protection, and access to justice. Professor Jiménez spent a year as part of the founding staff of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau where she worked on debt collection, debt relief, credit reporting, and student loan issues.

Ben Kaufman is the Director of Research & Investigations at the Student Borrower Protection Center. He joined SBPC from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau where he worked on issues related to student lending.

[1] The SBPC estimated in its report on misrepresentations related to bankruptcy that upwards of $50 billion in private credit may have been implicated. A quick estimate assuming ten-year amortization of these loans and a very conservative 6 percent interest rate yields more than $16.6 billion of interest charged that borrowers might have paid and deducted. Note that this amount is well below what the 2.6 million borrowers referenced in the SBPC report as being subject to misrepresentations around bankruptcy rights would have maximally been allowed to deduct over ten years at $2,500 per person per year ($65 billion).