By Ben Kaufman | March 13, 2020

New government data underscore that the student debt crisis is getting worse by the minute. These revelations should be front and center for policymakers as they consider bold action to protect borrowers from the economic effects of the global coronavirus pandemic. They should also present a warning to the giant student loan companies at the center of our broken student loan system: America cannot afford their shoddy servicing and bungled implementation of emergency debt relief programs.

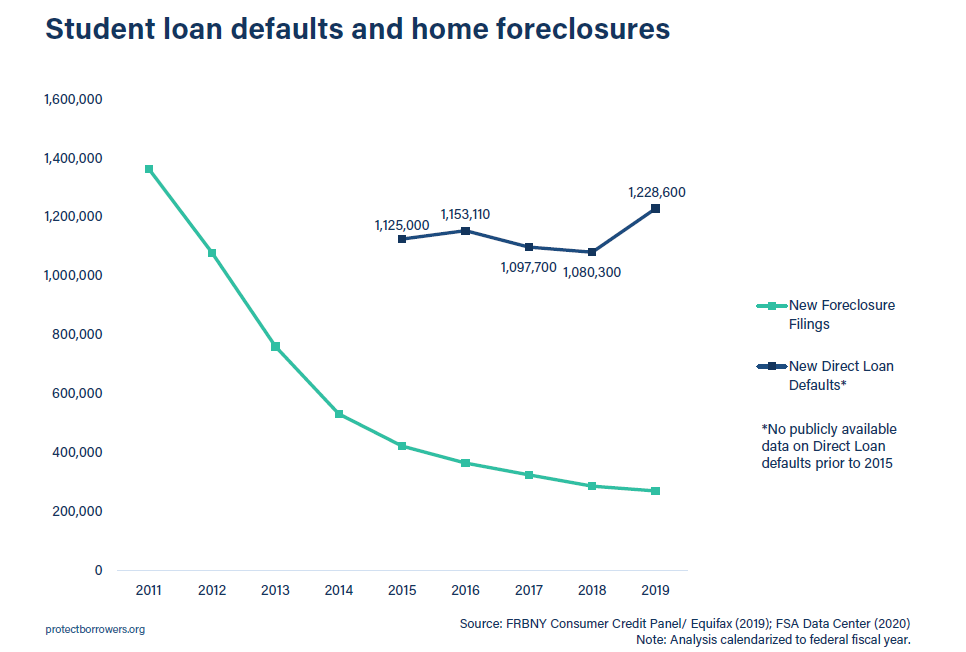

In particular, the Department of Education’s (ED) most recent quarterly update on its student loan portfolio contained a crucial number that seems to have gone widely overlooked: 1,228,600. That figure represents the cumulative total of unique federal student loan borrowers who defaulted on their loans (that is, reached a full 361 days of delinquency) during the 2019 federal fiscal year.

These new data indicate that defaults increased nearly 14 percent from 2018, where 1,080,300 borrowers defaulted on a federal student loan. In other words, during 2019, a borrower defaulted on a federal student loan every 26 seconds.

“…during 2019, a borrower defaulted on a federal student loan every 26 seconds.”

Beyond possibly costing borrowers thousands of dollars in accrued interest, these defaults cause countless additional spillover effects across borrowers’ lives, including making it harder for them to keep a job, to find a home, and even to maintain their physical health. In turn, these outcomes imply lasting damage for local communities and the economy as a whole, as research continues to show how student debt negatively impacts entrepreneurship, family formation, homeownership, and more.

In releasing its quarterly data, ED noted repeatedly (Quarter 2, Quarter 3, Quarter 4) that new defaults spiked “as a result of disaster-impacted borrowers exiting forbearance statuses.” Specifically, following “natural disasters such as Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria and the California wildfires,” borrowers’ loans were placed in mandatory administrative forbearance, or “forced-placed forbearance.” This means that borrowers’ loans were counted as being current without the borrower having to make any payments, something intended to help people deal with the fallout of a natural disaster.

However, complaints submitted by student loan borrowers to the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau demonstrate that borrowers frequently struggle to get back on track with their loans after experiencing a period of forced-placed forbearance, often due to sloppy or predatory student loan servicing practices (e.g., CFPB Complaint from a Navient Borrower Affected by Hurricane Maria, CFPB Complaint from a Nelnet Borrower Affected by California Wildfires).

Student loan servicers—the companies paid hundreds of millions of taxpayer dollars to help borrowers manage the repayment of their student loans—are tasked with implementing forced-placed forbearance and subsequently helping borrowers navigate the transition back into repayment. For example, a servicer might assist a borrower in Puerto Rico who is struggling after Hurricane Maria to enroll in one of the many affordable income-driven repayment (IDR) options to which they are legally entitled. These programs set borrowers’ monthly payment obligations at 10 percent to 20 percent of their discretionary income, including a $0 monthly payment option for borrowers who are unemployed or have very low wages. They also offer loan forgiveness after 20 to 25 years. Every single one of the 1,228,600 Americans who defaulted on a federal loan in 2019 was entitled to a range of default aversion options, and every single one failed to receive their benefits.

In the time it took you to read to this point, at least ten more borrowers defaulted on a federal student loan. It’s time for the Department of Education to take control of its contractors, for student loan servicers to be held accountable for their rampant failures, and for student loan borrowers to get the service they deserve.

###

Ben Kaufman is a Research & Policy Analyst at the Student Borrower Protection Center. He joined SBPC from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, where he worked as a Director’s Financial Analyst on issues related to student lending.