By Ben Kaufman | October 14, 2020

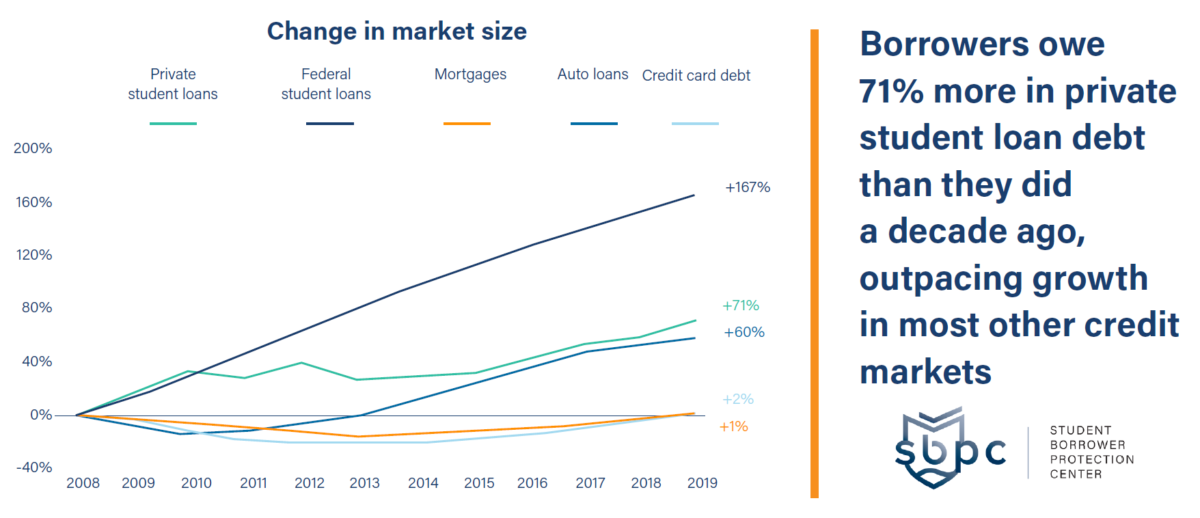

The private student loan market is often overshadowed by the much larger federal student loan market, and private student loans are routinely categorized by industry players as being free from borrower distress. However, as the SBPC highlighted earlier this year in a comprehensive report on the topic, the private student loan market is in fact a quickly expanding and harm-riddled area of the broader student debt ecosystem. Our report showed that private student debt is among the largest and fastest growing forms of consumer credit in the country, that borrowers regularly struggle under the weight of private student loans, and that a unique lack of protections and transparency provisions in the space is putting borrowers at risk. In particular, we showed how borrowers of color, and in particular Black borrowers, face disproportionate hardship when attempting to repay private student debt.

Findings from our report Private Student Lending

New data from the Federal Reserve’s Survey of Consumer Finances show that distress continues to mount in the private student loan market—especially for borrowers of color. The new data for 2019 point to borrower hardship and racial disparities that policymakers at all levels of government must take immediate action to address. Here are key takeaways from our analysis of the data:[1]

- Black borrowers with private student loans are in crisis. Almost 24 percent of Black borrowers with private student loans report having fallen behind on at least one private student loan due to economic hardship, nearly four times higher than the proportion of white borrowers. Information on borrower race is limited in the Federal Reserve’s public dataset, but the data indicate that roughly 16 percent of Asian, Indigenous, mixed-race, and other borrowers are also falling behind on their private student loans.

- Black borrowers with federal student loans are in distress, and Black borrowers with private student loans fare even worse. Existing research shows that Black borrowers face significant struggles with federal student loans relative to their peers. Our examination of the Federal Reserve’s new data confirms that finding, and also indicates that these disparities extend into—and are even more severe in—the private student loan market. The proportion of Black borrowers with private student loans who report having fallen behind—nearly 24 percent, as mentioned above—is almost double the proportion of Black borrowers with federal student loans who report similar distress. Together, our findings demonstrate that Black borrowers with private student loans face unique struggles that demand policymakers’ attention.

- Education is not “the great equalizer.” We regularly hear arguments that education alone is a “great equalizer” capable of eliminating racial inequities. However, for borrowers with private student loans—and especially for Black borrowers with private student loans who do not have graduate degrees—this is simply not the case. Black borrowers with private student loans who earned Bachelor’s degrees are roughly ten times more likely to have fallen behind than white borrowers with private student loans at the same level of educational attainment.[2]

It is important to note that these data were collected in 2019, long before the outbreak of the coronavirus. As we wrote in June, borrowers with private student loans were cut out of the federal protections of the CARES Act, and have been provided only limited, short-term relief on their loans during the pandemic—if they have gotten any relief at all. In light of this situation, it is likely that COVID-19 will only exacerbate the grim outcomes we see for borrowers with private student loans. Moreover, this pandemic has hit communities of color the hardest, with history showing that these are the same communities most likely to be denied the benefits of an eventual economic recovery.

It’s time to stand up for the nation’s more than six million borrowers with private student loans through comprehensive action at the state and federal level. It’s time to provide borrowers with private student loans the relief and protections they deserve. And most importantly, it’s time to acknowledge and address the unique struggles facing the borrowers of color bearing the brunt of the COVID-19 pandemic.

###

Ben Kaufman is a Research & Policy Analyst at the Student Borrower Protection Center. He joined SBPC from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau where he worked as a Director’s Financial Analyst on issues related to student lending.

[1] This analysis utilizes data from the Federal Reserve Board’s Survey of Consumer Finances (SCF). Following Gale, Gelfond, Fitchtner, and Harris (2020), we divide the SCF’s survey weight parameter (x42001) by five to produce summary statistics. Whether a borrower has private student loans is calculated by the answer to the question “How much is still owed on this loan?” for possible loans 1-6 if the answer to the question “Is this loan a federal student loan such as Stafford, Direct, PLUS, or Perkins?” is “No” for the associated loan. A borrower is coded as not currently making payments on at least one private student loan if they report having at least one private student loan that they are not making payments toward due to an inability to pay, the use of a forbearance, or the use of another debt forgiveness program (as determined by the question “(Are you/Is he/Is she/Is he or she) making payments on this loan now?”). The same process is replicated for federal student loans and for student loans in general to code borrowers as not currently making payments on a federal loan or a student loan generally (in the latter case, without considering their answer to the question “Is this loan a federal student loan such as Stafford, Direct, PLUS, or Perkins?”).

Race is based on the self-reported race of the head of household (x6809). Degree attainment is taken as the greater of the head of household’s highest level of educational attainment (x5931) or his or her spouse’s (x6111).

[2] Degree attainment is taken as the greater of the head of household’s highest level of educational attainment (x5931) or his or her spouse’s (x6111). Borrowers with less than some college are excluded. Note that insufficient data are available to produce a comparison for Latinx borrowers.