By Winston Berkman-Breen and Ben Kaufman | March 9, 2023

When Americans think about student debt, they are likely to imagine either federal student loans that are owed to the U.S. Department of Education or private student loans usually owed to a bank or credit union. But students can also end up in debt directly to their school via so-called “institutional debts” that arise when they have an unpaid bill or balance. Institutional debts can come from charges as small as a leftover library fee or for things as large as a shortfall in tuition payments, and schools can take extremely aggressive and harmful steps—including withholding students’ transcripts and credentials, or filing a lawsuit—when trying to collect on them.

Institutional debts can come from charges as small as a leftover library fee or for things as large as a shortfall in tuition payments, and schools can take extremely aggressive and harmful steps—including withholding students’ transcripts and credentials, or filing a lawsuit—when trying to collect on them.

Though institutional debts appear across the country, public reports have highlighted how they are a pervasive problem in Virginia. There, institutional debts have prevented students from graduating, and schools have been caught taking students to court and garnishing their wages over sometimes decades-old balances.

Luckily, Virginia lawmakers have taken action to protect borrowers. In its 2022 budget, the state’s General Assembly included language requiring Virginia’s Secretary of Education to examine and report on the situation surrounding institutional debt at the state’s public institutions of higher education, including providing detail on debt levels, borrower demographics, and school collection policies.

The Secretary of Education’s report came out in December 2022, offering a first-of-its-kind set of insights into institutional debt in Virginia. Unfortunately, it also appears to confirm many of the fears that motivated the General Assembly to act in the first place, with a massive and growing institutional debt burden disproportionately harming many of the most historically marginalized students.

Specific findings from Virginia’s report on institutional debt in the state include the following:

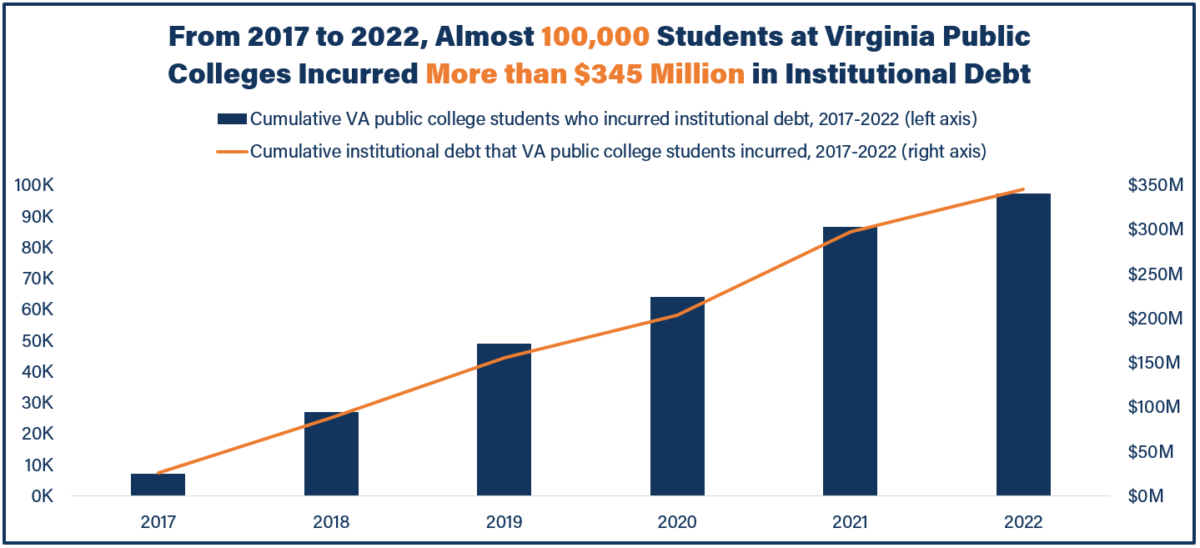

- Over the last 5 years, nearly 100,000 students at Virginia public colleges have incurred more than $345 million in total institutional debt. Across two and four-year institutions, 97,329 borrowers cumulatively incurred $345,503,884 in institutional debt to Virginia’s public colleges from 2017 to 2022. The state’s report notes, based on “discussion with institutions,” that these debts are most likely to be due to students having their financial aid eligibility or circumstances change, failing to secure funding such as by becoming unable to find a co-signer for a private student loan, withdrawing from a course after the “full refund” period, or incurring charges that “can include fines, parking tickets, or other costs…”

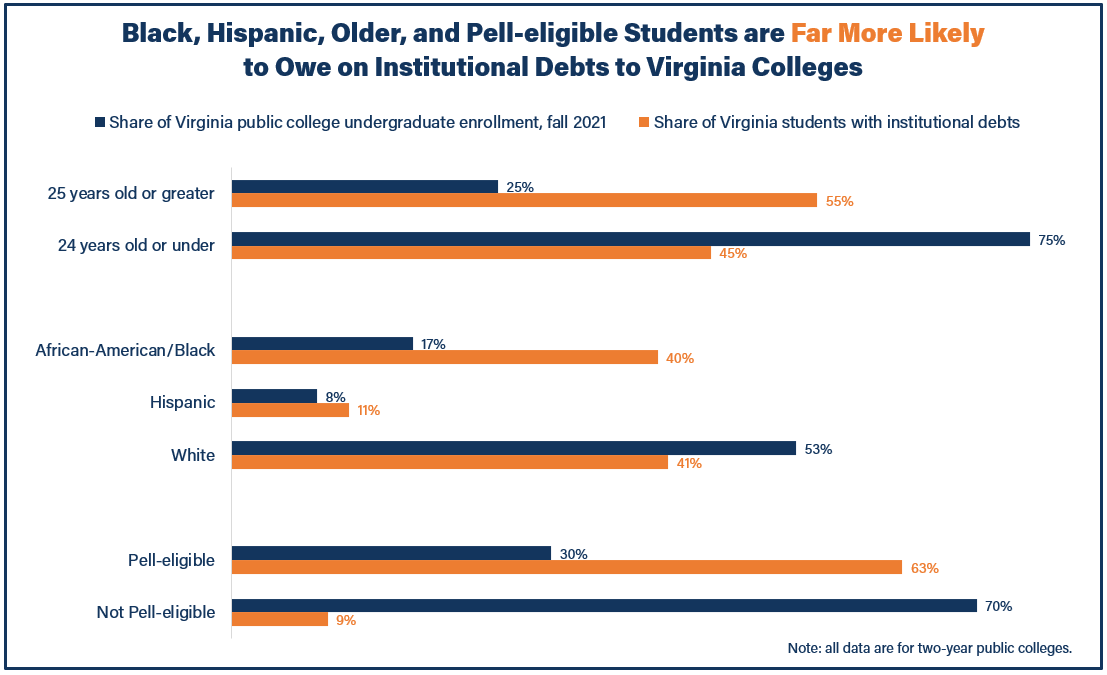

- Black, Hispanic,* older, and Pell-eligible students owe on an outsized share of institutional debt. Majorities of students at Virginia’s public two and four-year colleges are white, under 24 years old, and not eligible for Pell grants. However, those students who are Black, Hispanic, over 25 years old, and/or eligible for Pell grants represent a disproportionately large share of those who owe on institutional debts relative to enrollment levels. For example, while only 17 percent of two-year Virginia public college students enrolled in 2021 were Black, 40 percent of two-year Virginia public college students who incurred an institutional debt in the study period were Black.

- In all, Virginia identified 50,289 students over 25 who incurred more than $148 million in institutional debt, 21,913 Black students who incurred more than $66 million in institutional debt, 8,669 Hispanic students who incurred more than $29 million in institutional debt, and 34,638 Pell-eligible students who incurred more than $100 million in institutional debt.**

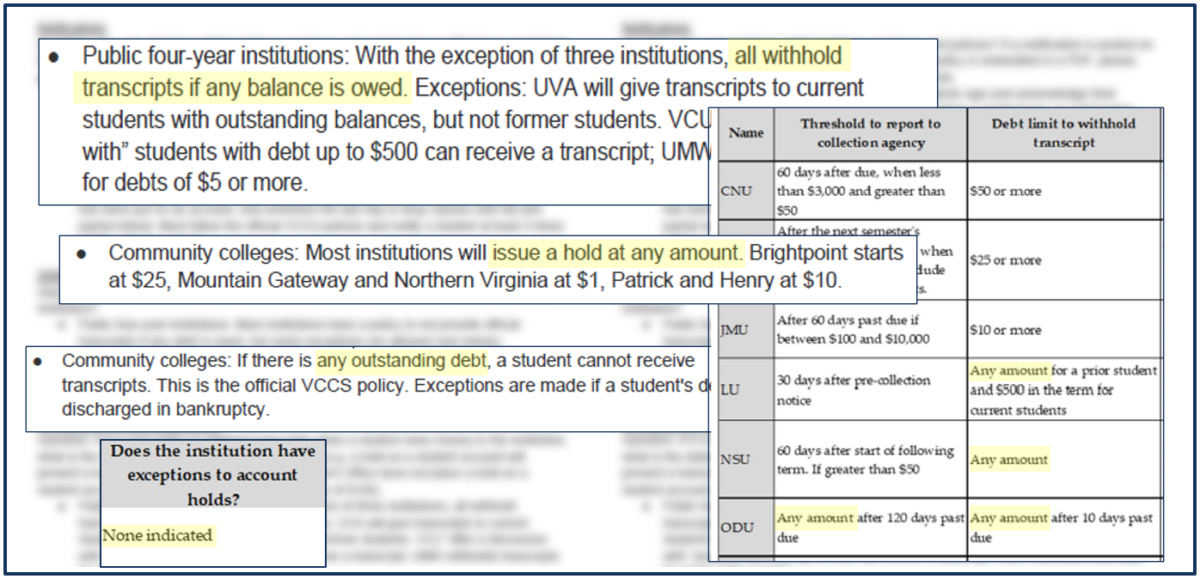

- Schools report using harsh collections measures, even for outstanding balances as small as $1. As part of its research, Virginia’s Department of Education surveyed colleges in the state on the policies and procedures they employ related to institutional debt. Questions in this survey pertained to the amount of debt necessary for a student to have before the school would take action against them, whether the shool withholds students’ transcripts until students pay their debts, whether schools have any unwritten policy by which they can work out an agreement with students who owe money, and more. Though responses varied, certain institutions reported that they initiate collection action for debts as small as $1, that they withhold students’ transcripts if they have any outstanding balance, and that they have no workaround policy. These measures appear to generally be harsher at two-year institutions, which pursue debts more aggressively even while serving a more financially marginalized student demographic.

Virginia’s findings paint a dire picture regarding institutional debt in the state. But the fact that the state has taken on this research in the first place marks a key first step toward solving the problem. With this information at hand, Virginia has a clear impetus for pursuing the strong reforms necessary to protect students from the harmful effects of runaway institutional debts.

States across the country can learn from this example. Lawmakers in New York, Maryland, and California have introduced legislation that would require schools to regularly provide the same types of data that Virginia included in its report. These common-sense bills would sunlight the financial relationships that already exist between schools and their current and former students, lending empirical support for calls for change that have historically been driven by individual students’ lived experiences. As we learn more about institutional debt, its scope, and its harms, decision-makers and the public will finally have the tools they need to push for change.

###

Winston Berkman-Breen is the Deputy Director of Advocacy & Policy Counsel at the Student Borrower Protection Center. Prior to joining the SBPC, Winston was the Director of Consumer Advocacy and Student Loan Advocate at the New York State Department of Financial Services.

Ben Kaufman is the Director of Research & Investigations at the Student Borrower Protection Center. He joined SBPC from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, where he worked on issues related to student lending.

* Racial category names reflect those used in the underlying report by Virginia’s Secretary of Education.

** SBPC calculations adding across two and four-year institutions.