By Bonnie Latreille and Persis Yu | November 18, 2025

This blog is part one of a three-part series that examines the shadow network of vendors that control the federal student loan market and the role they play in driving student loan defaults. It was cross-published by Debt Collection Lab here.

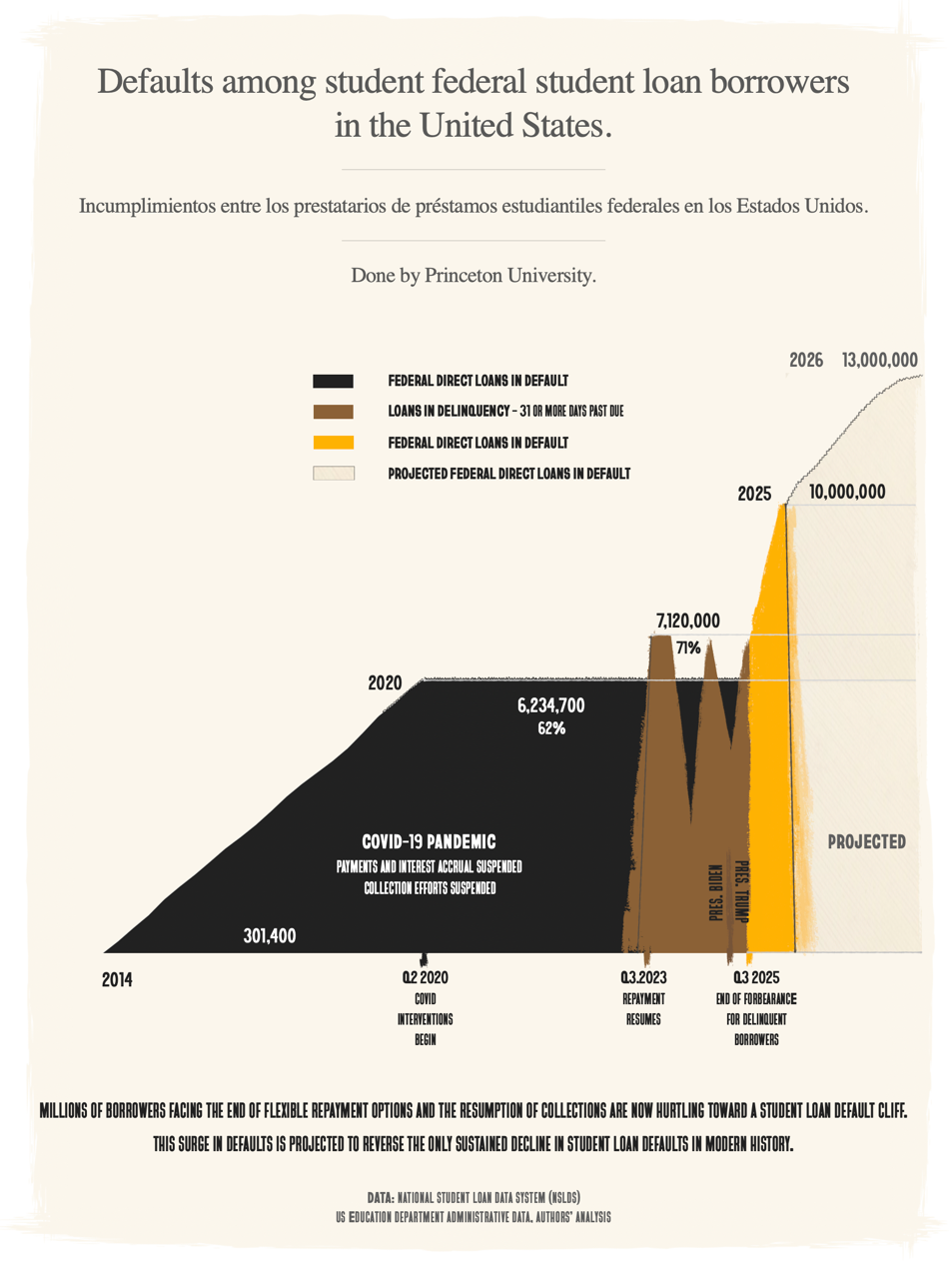

In a depressingly predictable turn of events, last month, approximately five million student loan borrowers likely defaulted on their loans. While the current government shutdown has delayed data releases, data are expected to show this wave of new defaults stacking atop the five million borrowers already in default, bringing the student debt crisis to an unprecedented level of distress. In total, roughly one-quarter of all federal student loan borrowers will face the fallout of defaulted loans, and if current delinquency trends hold, as many as 13 million borrowers may end up in default by the end of 2026. This outcome is a travesty, not only because the fallout from student debt can wreak havoc on borrowers’ lives, but also because this outcome was entirely preventable.

The student loan system is enormous, comprising the second-largest consumer credit market in America after mortgages. Total student debt across the U.S. now exceeds $1.8 trillion, which is more than auto loan debt and far more than total credit card debt. The U.S. Department of Education (ED) is the dominant player in this market, owning or backing roughly 92 percent of this debt (around $1.6 trillion). But ED doesn’t manage this vast portfolio alone. As will be discussed more in Part Two of this series, ED contracts out the day-to-day management of federal student loans to a sprawling network of private vendors that handle everything from loan origination to servicing and collections. In theory, this system of contractors is supposed to smoothly administer borrower benefits and protections. In practice, it has become a fragmented, opaque machinery that too often fails the very people it’s meant to serve—with millions of defaults as the result.

The Incredibly High Stakes for Student Loan Borrowers

Federal student loans are arguably both one of the safest consumer financial products and one of the most dangerous. On paper, student loan borrowers have a safety net of protections unparalleled in other credit markets. For example, the Higher Education Act guarantees every federal loan borrower the right to an Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plan—meaning your monthly payment can be capped at an affordable percentage of your income, no matter how large your balance is. If your college misled or defrauded you, you can apply to have the debt discharged under Borrower Defense rules. If you develop a disability that prevents you from working, you can stop payments and get your loans forgiven through a disability discharge. There are even provisions for loan forgiveness after 20–25 years of payments, or as little as 10 years for those in public service. With such robust consumer protections in place, some policymakers have argued that there should be a zero percent default rate.

Instead, America is now witnessing a default crisis of historic proportions. As of Fall 2025, ED’s own projections warned that 10 million student loan borrowers could now or soon will be in default. This grim prediction is rapidly becoming reality.

For context, even before the pandemic pause, default rates were disturbingly high—roughly 20 percent of borrowers were in default—but nothing like the scale we’re about to see. A 25 percent default rate in a federal credit program of this size is virtually unheard of. By comparison, during the subprime mortgage crisis, the delinquency rate on single-family home mortgages peaked at just under 12 percent, and the new foreclosure rate peaked at slightly over 2 percent. And yet, at that moment, policymakers recognized the crisis was a market failure, not an individual consumer failure, and designed interventions like the Home Affordability Modification Program, which reduced re-default by as much as 48 percent. Meanwhile, as the country dives into another recession, efforts to similarly support student loan borrowers have been fought tooth-and-nail at every step.

In other words, the policies of the Trump Administration are unnecessarily entrapping millions of Americans in default.

Why does this matter so much? Because a federal student loan default isn’t a mere financial technicality—it is a life-altering event. With any type of debt default, the fallout can be enormous: harassing collection calls, a trashed credit score, and even the threat of lawsuits. But with federal student loans, it’s all that and more. The entire weight of the federal government can bear down on defaulted borrowers through a suite of uniquely punitive collection tools. These include:

- Wage garnishment without a court order: The government can seize up to 15 percent of a defaulted borrower’s paychecks administratively, bypassing the normal court judgment process required for other debts. Once activated, the government is incapable of turning these garnishments off, even when required to do so by federal law, as evidenced by the Department’s filings in related litigation.

- Federal tax refund and benefit seizure: Through the Treasury Offset Program, ED can intercept federal payments to the borrower. This means seizing your federal tax refunds, including any Earned Income Tax Credit, and even slashing Social Security checks to collect on the debt. All without a day in court.

- Federal aid and housing penalties: Borrowers with a student loan in default lose eligibility for new federal student aid, cutting off the chance to return to school to finish a degree. They also won’t qualify for federally backed mortgages like FHA or VA home loans because a defaulted federal loan creates an automatic flag in the government’s credit reporting system, CAIVRS, which disqualifies them from these programs while the default remains.

- Professional license suspensions: Until recently, many states enforced laws that could revoke professional or driver’s licenses from individuals who defaulted on student loans. More than half of U.S. states had such policies on the books at one time, affecting nurses, teachers, and other licensed workers. Thankfully, in the last few years, many states have repealed these draconian laws after public outcry, but in some jurisdictions the threat still looms.

- Security clearance denial: Defaulting on a student loan shows up on your credit report and can jeopardize a borrower’s federal security clearance for sensitive jobs. Military service members, defense contractors, and government employees have learned the hard way that a default can stall or end their careers if it causes a clearance rejection.

- Acceleration and extra fees: Unlike a borrower who misses a few payments but can catch up, a defaulted borrower immediately has the entire loan balance declared “due in full.” Collection fees and interest capitalize, ballooning the balance owed.

- Legal action and even arrests: In extreme cases, defaulting on federal loans can entangle borrowers with law enforcement. There have been shocking reports of borrowers being confronted by police or U.S. Marshals at their homes over unpaid student loans. In 2016, a disabled veteran in Texas was even arrested by U.S. Marshals for a 30-year-old student debt—a sensational example that, while not common, underscores the harshness with which government-backed debt can be pursued.

In short, falling into default on a federal student loan can wreck a borrower’s financial life, and like all debts, can spill into their personal life in devastating ways.

“[Student] debt affects every part of my life. I have faced housing insufficiency and homelessness. I am unable to purchase a home or a car. I have been denied from specific jobs due to a credit check.” – Jay’Riah T. from California

The consequences are so severe that they often compound the original problem: a borrower in default might lose her job due to a lost clearance, license revocation, or poor credit, making it even harder for her to ever repay and get back on her feet. It’s a debt trap by design.

Private Companies Behind the Federal Curtain

Historically, ED has relied on a legion of private contractors to manage defaulted loans and chase down payments. At one point, approximately two dozen collection agencies had contracts to collect on federal student loan defaults. The Higher Education Act does give defaulted borrowers some eventual ways out of default and collection. For example, borrowers can complete a “rehabilitation” program where, after making nine on-time, voluntary payments, defaulted loans are reinstated to good standing. Alternatively, borrowers have the option to consolidate defaulted loans into a new federal student loan. ED’s vendors are supposed to help borrowers navigate and access those exits from default. But in practice, misaligned incentives, poor oversight, and sloppy contract requirements have meant that many collectors do a terrible job of guiding borrowers toward relief. Collection agencies get paid the most when they collect money, not when they help a borrower resolve their debt issues. Moreover, systemic problems in the federal procurement process often lead to a race to the bottom in service quality. For years, reports have found that some collectors actually discouraged borrowers from consolidating—instead pushing borrowers into loan options with higher rates of re-default, higher payments requiring borrowers to forgo basic needs in order to just pay as much as possible, and, incidentally, a higher payout rate for the collectors.

In one example, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) recently took action against one major debt collector, Performant Recovery, for “concoct[ing] a scheme to juice their profits” by deliberately delaying borrowers’ loan rehabilitation applications. Why would a collector delay helping someone out of default? Because under federal rules, if a defaulted Federal Family Education Loans (FFEL) borrower rehabilitates within 60 days, no collection fees are charged, meaning the collector misses out on a big commission. The CFPB found that Performant routinely stalled necessary actions (e.g., refusing to email forms, slow-walking paperwork) until enough time passed that a 16 percent fee could be added and paid to them. This abusive practice cost individual borrowers thousands in needless fees and kept them in default longer. The CFPB has now banned Performant from the industry altogether, but only after years of harm. Unfortunately, this kind of behavior by servicers and collectors—prioritizing short-term revenue over borrower success—is all too common.

A Broken Student Loan System Keeping Borrowers in Default

Much of the political rhetoric around student debt paints a picture of irresponsibility by implying that millions of borrowers are simply choosing not to pay their loans. If so many people default, the argument goes, it must be a moral failing or a refusal to “pay back what they took.” But that narrative is a myth. The evidence overwhelmingly shows that borrowers are trying to repay their loans and do attempt to use the tools provided to help them—yet the broken student loan infrastructure often thwarts their efforts.

Consider what has happened as loans transitioned back into repayment after the COVID-19 payment pause. During the pause (March 2020 to September 2023), borrowers were not required to pay, interest was reduced to 0 percent, and no one could newly default on a student loan. One might think that after such a long break, those who default now are simply unwilling to resume paying. In reality, the return to repayment has been marked by widespread confusion, servicer errors, and administrative failures that have pushed many into delinquency and default despite borrowers’ best efforts to make payments.

- Chaos in the restart: When bills resumed in Fall 2023, many borrowers never received a bill or got incorrect statements showing wrong amounts or due dates. Tens of millions of borrowers had their loans shuffled to new servicers during the pandemic; some borrowers say they never got notice of who their new servicer was. Others tried to set up autopay or IDR enrollment with their servicer, only to encounter non-functioning websites or customer service “doom loops” where calls went unanswered. Both the Federal Student Aid (FSA) Student Loan Ombudsman and CFPB Student Loan Ombudsman reported a record number of complaints detailing payment processing errors, lost paperwork, and unhelpful customer service that have “stymied [borrowers’] return to repayment.” Complaints described servicers misapplying payments and then hitting borrowers with delinquency notices or repeatedly calling servicers to fix mistakes and having to wait months for resolution. And while borrowers spend months of their lives trying to resolve these issues, interest accrues and credit scores tank.

“I’m never sure who to communicate with since my loans have been transferred… and I’m never sure what program will exist or be yanked away next.”

- IDR and relief programs in disarray: Many struggling borrowers have tried to enroll in IDR plans to get a lower payment only to find these options blocked or backlogged. In 2023, the Biden Administration rolled out the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE) plan, a more generous IDR plan that drew more than eight million enrollees. But by 2024, a lawsuit led to a court injunction halting SAVE. Shockingly, and contrary to any court orders, ED then froze all IDR enrollments. By August 2024, ED had ordered its vendors to stop processing any new applications for income-driven plans. As of early 2025, nearly 1.9 million borrowers were stuck in limbo, unable to even begin repayment on a reasonable plan because of this “processing pause.” Social media platforms and complaint forums were filled with stories of borrowers trying to do the right thing—submitting their income information, filling out pages of documentation, but ultimately hearing nothing for months, all while their accounts balances grew. Similarly, legal challenges nixed other debt relief efforts like one-time loan cancellation, breeding confusion and false hope. The rules of the game for borrowers have seemingly changed every few months, making it near-impossible for families to plan. One borrower’s frustrated comment captures it: “I’m never sure who to communicate with since my loans have been transferred… and I’m never sure what program will exist or be yanked away next.”

Servicing failures hit hardest in default management. For the approximately nine million borrowers who were in default before the pandemic, ED offered a “Fresh Start” initiative that offered borrowers a dramatically streamlined path out of default. In theory, it was a golden opportunity to wipe the slate clean. In practice, less than one million borrowers opted in. Outreach about Fresh Start was limited and borrowers were required to take affirmative steps to fully take advantage of the program. As a result, many defaulted borrowers never got the memo or couldn’t navigate the process to opt in. And those who remain in default have been encountering the same old problems: collection contractors that don’t answer the phone or fail to explain options.

At the end of the Biden Administration, federal officials acknowledged that the default inventions like Fresh Start were insufficient and substantial obstacles remained for borrowers seeking to get out of default. In some cases, borrowers trying to access these programs were put on hold until they gave up. These failures are especially pronounced for vulnerable borrowers, such as older borrowers, borrowers with disabilities, and those who didn’t complete their degrees and do not fully benefit from the debt they took on.

Crucially, many of the “failures” in the student loan market are by design or incentive. The contractors servicing these loans operate under complex, sometimes perverse incentives set by their contracts. As noted earlier, debt collectors have incentives to delay rehabilitation or discourage consolidation altogether. Regular loan servicers historically were paid a flat monthly fee per account—whether the borrower was repaying or not—which did not always reward intensive help for those in trouble. Only recently has ED begun adjusting contracts to emphasize default prevention outcomes, like giving servicers credit for keeping borrowers in good standing. Yet at the same time, it has launched a new contract model that is already cracking under the stress of the broken student loan system, as will be discussed in Part Two.

Meanwhile, oversight of these contracts by ED has been lax for years, and most recently, nonexistent. It took high-profile lawsuits and enforcement actions to expose some of the worst practices. For example, Navient—once one of the largest federal loan servicers—was found to have steered countless borrowers into costly forbearances instead of guiding them into affordable IDR plans. This practice padded Navient’s bottom line but left borrowers worse off with accumulated interest. In 2024, the CFPB finally banned Navient from federal servicing and fined it $120 million, stating that Navient had “illegally deprived borrowers of opportunities to enroll in more affordable plans and forced them to pay much more than they should have.” Such accountability came only after years of damage, and the settlement amounts barely scratched the surface of the financial harm done to borrowers.

But Navient was hardly alone. Other servicers and collectors have faced lawsuits for similar failures to effectuate borrowers’ rights. These lawsuits have, at least twice, played a large role in driving two of the largest players out of the federal student loan market, which in turn places more loan volume and more risk in the remaining vendors. When these vendors become too big to fail, ED has repeatedly demonstrated that it is unwilling to spook them by actually enforcing contractual penalties. Instead, it waives contract requirements that are specifically designed to improve borrower outcomes.

The end result of these systemic problems is that millions of borrowers who should have been able to avoid default were not given a fair chance to do so.

The current wave of defaults, therefore, is not a surprise—it’s a policy failure years in the making. It’s the predictable result of a loan repayment system that was overly complex, often punitive, and poorly managed by a tangle of contractors without adequate accountability. And it was all utterly preventable. Had ED fixed servicer incentives and cleaned up the default process earlier; had it streamlined access to IDR and automatically enrolled struggling borrowers; had it extended more relief before millions in default—America would not be watching this catastrophe unfold. And now, the default crisis arrives as a perfect storm of economic distress hits American families.

An Economic Earthquake

Finally, policymakers must recognize that this default wave is cresting at a time of broader economic uncertainty. The current economic climate is making things worse. Inflation and tariffs are driving up the cost of living, and many borrowers depleted savings just to get by during the pandemic. Now, interest rates are higher on mortgages, car loans, and credit cards, squeezing household budgets from all sides. A recent Protect Borrowers and Groundwork Collaborative poll found that nearly a quarter of voters say that they would need a windfall—an inheritance, government assistance, or a winning lottery ticket—to ever get out of debt, and an alarming number of consumers are taking on debt to pay off other debt. The CFPB warned in mid-2023 that more than 1 in 13 student loan borrowers were already behind on other debts like credit cards—a higher rate than before the pandemic. About 1 in 5 borrowers had other risk factors like increased debt burdens, indicating that they would struggle when student loan bills returned. This has proven true: as student loan payments turned back on, delinquency rates for credit cards and auto loans also climbed, suggesting many borrowers simply cannot cover everything. The United States government is essentially asking millions of Americans to restart sizable loan payments in the aftermath of a pandemic, amid higher inflation, mass unemployment, a federal government shutdown that has exacerbated customer service issues at ED vendors, and with no meaningful additional support. It is the perfect storm for defaults. And unlike in 2020, there are no stimulus checks or extra unemployment benefits coming to the rescue. Without intervention, the student loan default cliff will be a drag on the economy—reducing consumer spending and diverting dollars from productive uses like home-buying or investing in small businesses into fruitless collection efforts.

The wave of student loan defaults sweeping the country right now is both a social crisis and a policy failure. It was predictable, and it was preventable. Millions of borrowers did everything that was asked of them—they took on the debt in good faith to pursue education, they tried to navigate a confusing system to repay that debt—yet they’re the ones bearing the brunt of this failure. This moment demands urgent attention from lawmakers, education leaders, and the loan industry.

Without dramatic intervention, mass default will be the “new normal.” The costs to individuals, communities, and the nation are simply too high. Instead, this should be a wake-up call to fix what’s broken in the federal student loan system. That means enforcing accountability at every level—federal, state, local, and private. It also means setting and performance standards for servicers and collectors, streamlining access to affordable repayment plans, and removing punitive policies that needlessly ruin lives. Most importantly, it means rethinking how America finances higher education so that student debt isn’t a debt sentence.

In the next parts of this series, the authors will dive deeper into the who behind this crisis—examining the web of contractors and vendors that profit from the student loan system, often at borrowers’ expense—and discuss how various interventions, from federal policy to private litigation, have shifted the way the market thinks about student loan defaults. For now, the student loan default cliff is here; how policymakers respond will determine the financial futures of a generation. It’s time to act with the urgency and compassion this crisis demands.

Part Two of this series will explore how federal loan servicers and collection agencies operate as the “shadow” system underpinning student loans, contributing to the default epidemic. Part Three will discuss the successes of various policy, legal, and operational interventions in the student loan default market.

###

Bonnie Latreille is a visiting Senior Fellow with the Debt Collection Lab at Princeton University. She was the former Student Loan Ombudsman for the U.S. Department of Education and has spent more than a decade helping borrowers navigate the pitfalls of the student loan system.

Persis Yu is the Deputy Executive Director and Managing Counsel at Protect Borrowers. Persis is a nationally recognized expert on student loan law and has over a decade of hands-on experience representing borrowers.