The following Protect Borrowers Deep Dive is an updated analysis of certain student loan-related provisions of the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” passed by Congress and signed into law through the budget reconciliation process. An original analysis focused on the House version of the bill was published on May 6, 2025.

Author: Jennifer Zhang, September 11, 2025.

Jump to:

- Introduction

- Capping Access to or Eliminating Federal Student Loan Programs

- Raising Federal Student Loan Costs for New Borrowers

- Raising Federal Student Loan Costs for Current Borrowers

- Payments for Current Borrowers Under the IBR Plan

- Raising Costs for Parent Borrowers

- Leaving Borrowers with a Massive Tax Bill

- Conclusion

Introduction

On July 4, 2025, President Trump signed into law the congressional budget reconciliation bill known as the “One Big Beautiful Bill Act” (OBBBA) that makes significant cuts to long-standing safety net programs in order to offset $4 trillion in tax breaks for billionaires and the biggest corporations. The OBBBA slashed nearly $300 billion from federal financial aid and the student loan program, largely through eliminating certain loan programs, limiting how much students and families can borrow from the federal government, and making it much more expensive for millions of borrowers to repay their federal student loan debt. Additionally, the OBBBA gutted Medicaid by nearly $1 trillion, which is estimated to force 16 million Americans off their health insurance, and cut the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) by $186 billion while transferring a substantial portion of SNAP spending to states. As a result, state legislatures—already facing massive budget shortfalls—are likely to make substantial cuts to state higher education funding, which will likely lead to even higher tuition costs, enrollment declines, cuts to essential student services, and lower quality education across the board.

More specifically, the OBBBA:

- Reduces access to higher education financing for students and families, by:

- Placing new caps on federal borrowing including on graduate unsubsidized loans, professional unsubsidized loans, Parent PLUS loans, and placing a lifetime limit on student loan borrowing for all borrowers; and

- Eliminating the Graduate PLUS loan program.

- Raises student loan costs for current borrowers (who took out loans before July 1, 2026 and are not Parent PLUS borrowers) by:

- Phasing out the Saving on a Valuable Education (SAVE), Pay As You Earn (PAYE), and Income-Contingent Repayment (ICR) plans by July 1, 2028;

- After July 1, 2028, pushing current borrowers out of their Income-Driven Repayment (IDR) plans and into either Income-Based Repayment (IBR) or the more expensive Repayment Assistance Plan (RAP).

- Raises student loan repayment costs and eliminates critical protections for new borrowers (who take out loans after July 1, 2026) by:

- Eliminating their access to all current IDR plans;

- Providing borrowers with only two repayment options—a new Standard Plan and a more expensive and less generous RAP; and

- For borrowers who take out loans after July 1, 2027, eliminating access to unemployment and economic hardship deferments, which allow borrowers to pause their payments for up to three years, and limiting the time a borrower can be in forbearance to no more than nine months in any two-year period.

- Raises student loan costs for Parent PLUS borrowers (who take out or consolidate their loans after July 1, 2026) by depriving them of access to any IDR plan, and only allowing them to repay loans through the new Standard Plan.

- Leaves a massive tax bill for borrowers who have earned IDR loan cancellation under the law, by failing to extend the comprehensive exclusion of cancelled student loan debt from being considered as income for federal tax purposes under the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021.

This is not an exhaustive list of the OBBBA’s higher education provisions, but an overview of some of the changes for which we provide economic analyses and projected calculations of the impact upon borrowers. For additional information on the OBBBA’s delay of the implementation of regulations that help defrauded borrowers access student loan debt discharge and new earnings threshold accountability test for higher education institutions, see a related analysis by The Institute for College Access & Success. For a guide on what borrowers can do in response to these changes, see our “What Borrowers Need to Know” article and our blog, which will be updated with additional entries as more information comes out about how the bill will be implemented. Borrowers can also contact their members of Congress using our congressional casework tool if they encounter any issues with handling their student loans.

Capping Access to or Eliminating Federal Student Loan Programs

The OBBBA sets a suite of new caps on federal student loans. Parents, graduates, and professional students were previously permitted to borrow federal Direct PLUS loans up to an institution’s cost of attendance. Under the new law, the Graduate PLUS program will be entirely eliminated for students enrolling in programs after July 1, 2026; Parent PLUS loans will be capped at $20,000 annually (up to $65,000 total per enrolled dependent); the lifetime cap on graduate unsubsidized loans will be lowered to $100,000 (down from $138,500); and a new lifetime aggregate borrowing cap of $257,500 will be placed on all students (not including Parent PLUS loans).

Some proponents of capping federal loans have argued that allowing too much access to federal loans encourages institutions to increase the cost of college, and therefore capping federal loans would lower costs. There is ample empirical research demonstrating that this is not the case, and that for-profit institutions are the most likely to try to squeeze every last dollar out of both federal student loan packages and veterans with GI Bill benefits. Yet, the OBBBA does nothing to force for-profit institutions to bring down costs. In fact, the new law will make it even easier for for-profit colleges to take advantage of their students and leave them drowning in debt, such as by delaying the implementation of rules like Borrower Defense to Repayment, which are intended to hold schools accountable and provide borrowers relief when they are defrauded.

In any case, limiting access to federal loans without investing in grants and other financial aid, or capping how much tuition institutions can charge, is like filling a car with less gas, but not making the trip any shorter.

Facing new limits on federal loans, students will be forced to seek out loans from the private market, which generally restricts lending to creditworthy borrowers with cosigners and is much harder to access. Private loans are also more expensive, contain fewer consumer protections, and are ineligible for critical pathways to cancellation. Borrowers denied private loans—who will disproportionately be students of color and from lower–income families—may give up on pursuing higher education altogether, or fall victim to predatory lenders and for-profit programs that deceive and saddle them with large amounts of debt and useless degrees.

Eliminating the Graduate PLUS loan program will make paying for graduate and professional education more expensive.

- Over 440,000 borrowers took out Graduate PLUS loans in Award Year (AY) 2023-2024, with an average balance of $31,809.1 For degree-holders who rely on Grad PLUS, it makes up nearly half (47 percent) of the typical graduate borrower’s loan package. Given the elimination of the Grad PLUS loan program, these borrowers will have to seek out options in a much more expensive and exclusive private market.

- The average Graduate PLUS borrower who replaces their entire loan with a private market option would pay an additional $10,885 in interest, generously assuming that they repay the full balance in 10 years.2

- An average master’s degree student who both takes out unsubsidized graduate Stafford loans and replaces their Graduate PLUS borrowing with a private loan would be forced to make two types of payments each month and see their total monthly student loan costs skyrocket. Prior to the OBBBA, graduate students could take out both unsubsidized graduate Stafford loans (up to $20,500) and Graduate PLUS loans (up to the cost of attendance) each year, and repay both loans with a single monthly payment under an IDR plan. As a result of OBBBA, the borrower would be forced to make a monthly payment under RAP or the new Standard Plan for their graduate unsubsidized loan, plus a much higher amount for their private loan. This would cost the typical such borrower at least an additional $755 and up to $1,034 more each month, totaling between $9,055 to $12,407 more per year.3

Limiting access to Parent PLUS loans will push more families into the more expensive and risky private loan market.

- Between 29 percent to nearly half of Parent PLUS borrowers may be forced to turn to private loans each year due to the OBBBA’s new $20,000 annual loan cap. Approximately 17.1 percent of Parent PLUS borrowers may exceed the $65,000 cumulative loan cap and would need to turn to private loans for funding.4

- The average Parent PLUS borrower who exceeds the $65,000 per-dependent student cap and makes up the gap with private loans would pay an additional $4,608 in interest, generously assuming that they repay the full balance in 10 years.5

Raising Federal Student Loan Costs for New Borrowers

The OBBBA will substantially increase student loan costs for borrowers who take out loans after July 1, 2026. It does this by eliminating their access to all current Income-Driven Repayment (IDR plans and forcing them to choose between either the new Standard Plan or a RAP—which is more expensive than almost every existing IDR plan and requires borrowers to be in repayment for 30 years before being eligible for cancellation, rather than 20-25 years.

Payments for New Borrowers Under the Standard Plan

Like the current Standard Plan, the new Standard Plan is calculated based upon the borrower’s loan balance and does not adjust monthly payments based on the borrower’s income. It calculates payment amounts based on the amount a borrower owes at the time of repayment and a predetermined, fixed repayment term. Those borrowing up to $25,000 will have 10 years; between $25,000 to $50,000 have 15 years; $50,000 to $100,000 have 20 years; and over $100,000 have 25 years to repay.

- The average bachelor’s degree holder enrolled in the new Standard Plan will pay $324 per month or $3,887 annually, for 15 years.6

- The average graduate degree (MA/MS) holder will pay $449 per month or $5,388 annually, for 20 years, in addition to any payments owed for their undergraduate education.7

- The average professional degree holder will pay $1,303 per month or $15,639 annually, for 25 years, in addition to any payments owed for their undergraduate education.8

Payments for New Borrowers Under the RAP Plan

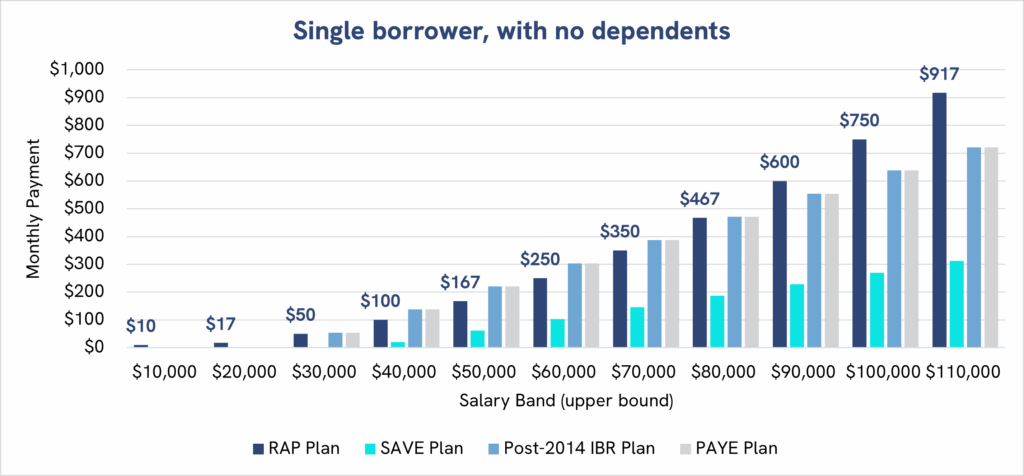

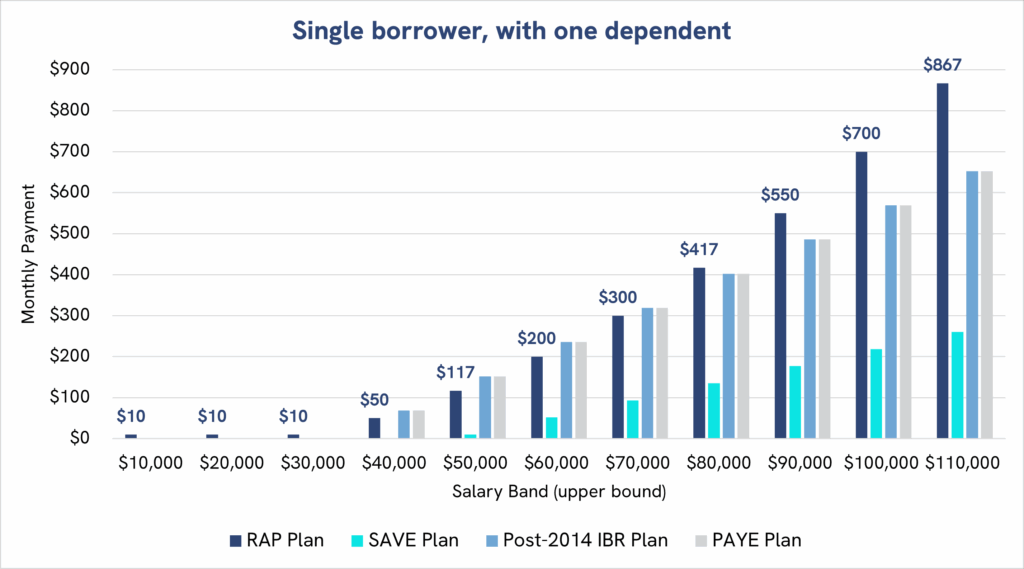

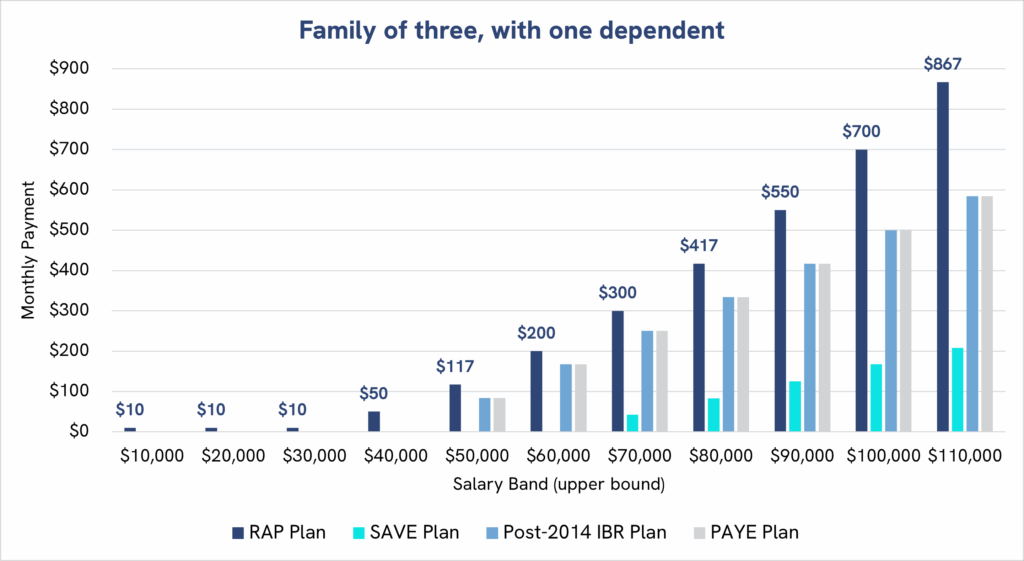

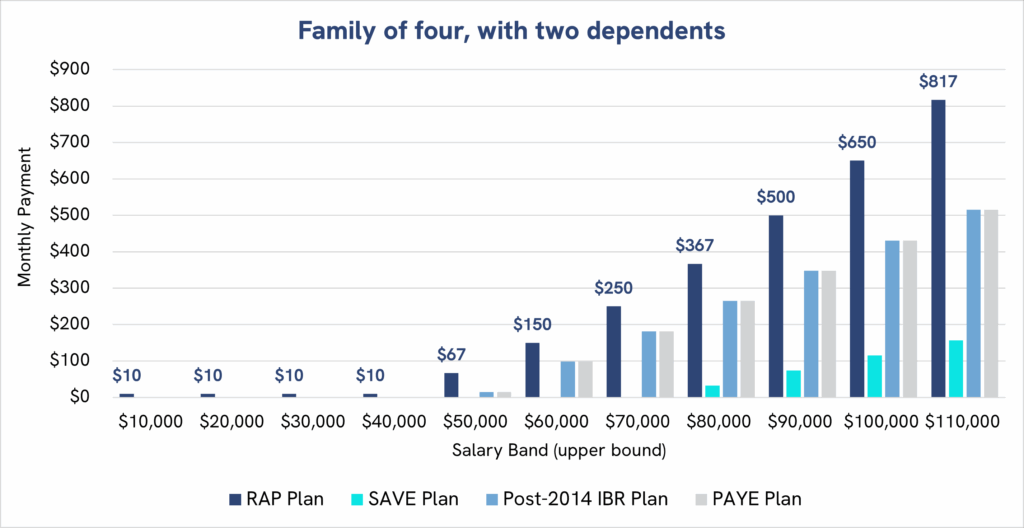

For new borrowers, the OBBBA eliminates all current IDR plans and replaces them with a single income-cognizant plan, which is available to borrowers who do not want to repay their balance under the Standard Plan (see above). This Repayment Assistance Plan forces borrowers to make more expensive monthly payments than almost every current IDR plan that it replaces. Enrolled borrowers would pay between 1 to 10 percent of their adjusted gross income, depending on how much they make, requires all borrowers to make a minimum monthly payment of $10 (regardless of whether a borrower is significantly low-income or unemployed) and includes a $50 monthly payment reduction per dependent child (see our “What Borrowers Need to Know” article for more information).

- A typical single borrower with a bachelor’s degree would pay $4,168 more per year compared to the SAVE Plan. The RAP Plan would force them to pay $535 each month, compared to $188 under the SAVE Plan—a monthly increase of $347.9

- A typical single borrower with some college but no degree would pay $1,761 more per year compared to the SAVE Plan. The RAP Plan would force them to pay $221 each month, compared to $74 under the SAVE Plan—a monthly increase of $147.10

- A typical family of four headed by a borrower with a bachelor’s degree would pay $4,824 more per year compared to the SAVE Plan. The RAP Plan would force them to pay $435 each month, compared to $33 under the SAVE Plan—a monthly increase of $402.11

- A typical family of four headed by a borrower with some college but no degree would pay $1,452 more per year compared to the SAVE Plan. The RAP Plan would force them to pay $121 each month, compared to $0 under the SAVE Plan—a monthly increase of $121.12

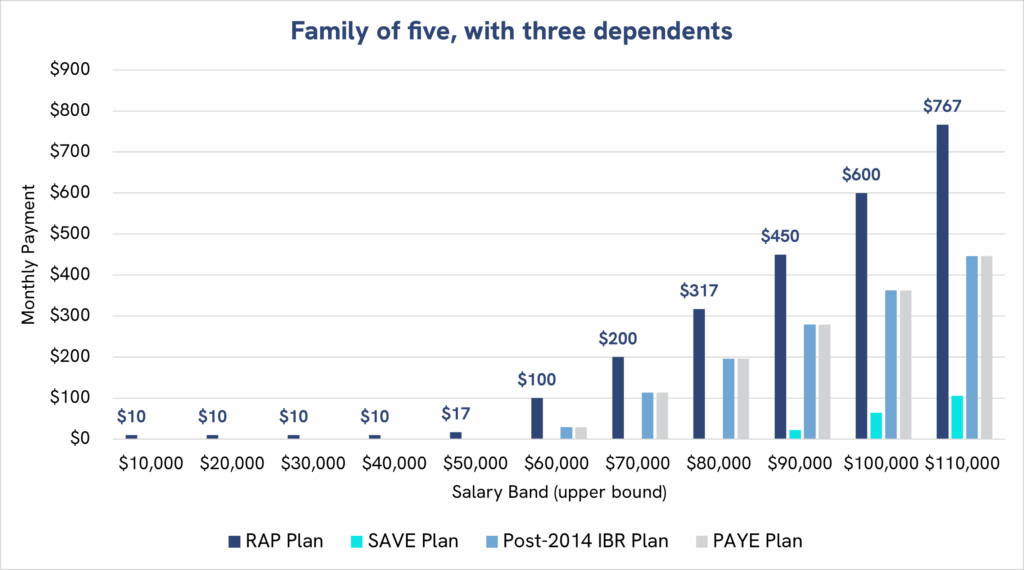

The following charts illustrate how RAP imposes higher monthly costs for borrowers and their families than almost every other payment plan.

On top of this, borrowers enrolled in RAP must make payments for 30 years before being eligible for loan cancellation, compared to 20 to 25 years under IDR plans and as little as 10 years under SAVE. This would saddle borrowers with a significant amount of debt for the overwhelming majority of their professional careers and cost significantly more over the life of the loan. The RAP Plan is also now the only payment plan available to new borrowers that is eligible for Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF).

Raising Federal Student Loan Costs for Current Borrowers

For current borrowers of loans other than Parent PLUS, the OBBBA allows them to remain on their current repayment plans until no later than July 1, 2028. After that date, these borrowers will be forced to choose between either the new Standard Plan, the new RAP Plan, or the current IBR plan. Borrowers who do not make a selection will be automatically placed on the RAP Plan or, if they are ineligible for the RAP, IBR.

Current borrowers who enroll in the Standard Plan and RAP are projected to pay the same monthly amounts as new borrowers for the remainder of the life of their loans.

Payments for Current Borrowers Under the IBR Plan

- A typical single borrower with a bachelor’s degree would pay $3,425 more per year compared to the SAVE Plan. The IBR Plan would force them to pay $473 each month, compared to $188 under the SAVE Plan—a monthly increase of $285.13

- A typical family of four headed by a borrower with a bachelor’s degree would pay $2,806 more per year compared to the SAVE Plan. The IBR Plan would force them to pay $267 each month, compared to $33 under the SAVE Plan—a monthly increase of $234.14

Raising Costs for Parent Borrowers

Parent PLUS borrowers with loans borrowed prior to July 1, 2026, can remain on their current plans until no later than July 1, 2028. After that date, they will be placed into the IBR plan. Current Parent PLUS borrowers who are not already enrolled in ICR must consolidate their loans before July 1, 2026, in order to enroll in IBR—they will not have access to RAP. Borrowers who take out Parent PLUS loans after July 1, 2026, or who do not take such steps to retain access to IBR, will only be able to repay their loans on the new Standard Plan.

Even though RAP is significantly more expensive than almost every current Income-Driven Repayment plan that it replaces, excluding future Parent PLUS borrowers from accessing it and forcing them to repay on only the Standard Plan will cause significant additional economic harm to the lowest-income families.

- Most Parent PLUS borrowers receive Pell Grants as part of their student’s financial aid package, meaning they generally make under $40,000 and are among the lowest-income and lowest-asset families. Parent PLUS recipients are also disproportionately from families of color; 6.2 percent of Black students had a parent who took out Parent PLUS loans in 2018, compared to 5.1 percent of white students.

- Parent PLUS loans are only a small part of the total debt burden taken on by families. In AY 2015-2016, undergraduate students who used Parent PLUS had, on average, $29,000 in Stafford loan debt, $33,000 in Parent PLUS debt, and $4,000 in private loan debt, totaling $66,000. These figures have likely climbed significantly over the last decade. Since Parent PLUS loans are taken out by parents, this debt burdens the student’s entire family and can have lasting financial consequences.

- A typical Parent PLUS borrower would pay $1,427 more per year under the Standard Plan compared to the ICR Plan. The Standard Plan would force them to pay $250 each month, compared to $131 under ICR—a monthly increase of $119.15

- A typical Parent PLUS borrower would pay $2,000 more per year under the Standard Plan compared to the RAP Plan. The Standard Plan would force them to pay $250 each month, compared to $167 under RAP—a monthly increase of $83.16

Leaving Borrowers with a Massive Tax Bill

Federal loan borrowers enrolled in IDR plans are entitled to cancellation after 20 to 25 years in repayment. Under the American Rescue Plan Act passed by Congress in 2021, Congress ensured that cancelled student loan debt would not be considered income for federal tax purposes until December 31, 2025. The OBBBA failed to extend this protection for borrowers, except for loans cancelled due to death or disability. Cancellation under Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) and school-related discharges are not subject to federal taxes. However, borrowers that qualify for cancellation under any IDR plan after January 1, 2026 may face a massive federal tax bill.

- Roughly two-thirds of IDR loan cancellation recipients make less than $50,000, according to a student loan borrower survey conducted by the CFPB from 2023 to 2024. These borrowers are at the 38th household income percentile and make less than 62 percent of American households.

- IDR loan cancellation recipients received an average of $49,321 in cancelled student loan debt, according to the Department of Education.

- Most borrowers who receive loan cancellation and would be subject to the new income taxes would be financially devastated by a tax surge. A reported increase of $20,000 to $40,000 in income would lead to thousands of dollars in additional federal taxes. However, 64 percent of IDR loan cancellation recipients have less than $1,000 in savings, and 81 percent have less than $5,000 in savings. The coming tax bill will exhaust the savings of many borrowers and likely push them into further debt.

Conclusion

The OBBBA will have financially devastating consequences for borrowers, students, and their families and will make paying for college more expensive and risky. Millions of borrowers will be pushed toward costlier federal loan repayment plans, regardless of when they took out their loan. New caps on graduate, professional, and aggregate borrowing will push students into a selective private market that prioritizes lending to affluent families while reserving the most predatory debt traps for low-income borrowers. As a result, many Americans will be pushed into lifelong debt traps or out of higher education altogether. These changes, alongside billions of dollars of cuts to SNAP and Medicaid, will further jack up costs for working families—all to pay for massive tax cuts for billionaires and corporations. For the millions of Americans struggling to pay for college, keep up with their student loans, and simply make ends meet, the OBBBA pushes prospects of economic mobility and achieving the American Dream further out of reach.

Jennifer Zhang is a Research Associate at the Student Borrower Protection Center. Prior to joining SBPC, she was a Director’s Financial Analyst at the CFPB, where she worked with the Student Loan Ombudsman’s office, the Policy Planning & Strategy team of the Director’s front office, and the Quantitative Analytics team of the Enforcement Division.

Endnotes: ⬆

- In AY 2023-2024, there were 444,452 Graduate PLUS loan recipients and a total of $14,137,455,017 in Grad PLUS loans originated. This averages out to $31,808.73 per recipient. See U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, Data Center (archived link). ↩︎

- We calculate this assuming the borrower finds a private graduate student loan with an interest rate of 9.93 percent, which is the weekly average at the time of writing this analysis, after having lost access to Graduate PLUS loans, which had an average interest rate of 7.27 percent over the decade from AY 2015-2016 to AY 2025-2026. See Business Insider (archived link); U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid (archived link); Education Data Initiative. We additionally assume that this is a fixed interest rate, though the aforementioned private rate is variable (which are generally lower than fixed rates), and that the interest rates of both Graduate PLUS and the private loan do not change across the two academic years. The additional interest is calculated for a principal of $63,618 (twice the annual Grad PLUS loan amount originated per borrower of $31,809, since most graduate programs take two years to complete), a repayment period of 10 years, the assumption that the borrower repays the loan in full, and (for simplicity) the assumption that interest does not accrue and the borrower does not have to begin repayment until after they complete their degree. If this last assumption is negated, the total interest paid and the difference between the two loan types would be greater. The borrower would pay $26,087.04 in interest on the Graduate PLUS loans, and $36,972.30 in interest on the private graduate loans, leading to a difference of $10,855.23. ↩︎

- We calculate this by assuming that the master’s degree holder is single, has no dependents, and makes the median income of master’s degree holders in 2024 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics ($95,680). We assume the borrower is a typical Graduate PLUS borrower, who maximizes the $20,500 pre-OBBBA annual limit on graduate unsubsidized loans before taking out the mean Graduate PLUS loan amount of $31,809 each year, adding up to a total loan package of $104,618 for two years. Before the OBBBA, the borrower would be eligible to repay both these loans using a single monthly payment of $601.71 under the IBR plan (the most affordable option of the available IDR plans). As a result of policy changes in the OBBBA, the borrower would still be able to maximize the $20,500 in annual graduate unsubsidized loans, but would have to find a private market loan to replace what they would have taken out in Graduate PLUS loans ($63,618 across two years). We assume they would repay the private loan at the average private market interest rate of 9.93 percent on a standard amortization schedule with a term of 10 years, and that the rate remains the same for loans disbursed across all years.

For the lower-bound estimate, we assume the borrower would pay down their $41,000 in graduate unsubsidized loans on the OBBBA’s new Standard plan at $838.25 per month, and make an additional payment of $838.25 per month for their private loan, totaling $1,097.27 each month. We assume this loan has an interest rate of 8.94 percent (the Grad PLUS interest rate in AY 2025-2026) across both years.

For the upper-bound estimate, we assume the borrower would pay down their $41,000 in graduate unsubsidized loans on the OBBBA’s RAP plan at $797.33 per month, and make an additional payment of $838.25 per month for their private loan, totaling $1,635.59 each month.

In short, the borrower would have been able to pay for their graduate school with $601.71 per month before the OBBBA, but now must pay either $1,356.29 (if they elect for the Standard plan for their graduate unsubsidized loan) or $1,635.59 per month (if they elect for the RAP plan). This is a monthly increase of $754.58 or $1,033.88, and an annual increase of $9,055.01 or $12,406.53, respectively. See Bureau of Labor Statistics (archived link); Business Insider (archived link); U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid (archived link); Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. ↩︎ - The “29.0 percent” figure paraphrases the research of the Century Foundation, where the author found the percent of Parent PLUS borrowers who borrowed more than $20,000 in AY 2019-2020 using National Postsecondary Student Aid Study data via National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) Datalab (retrieval code: qeppgq). This is likely a lower-bound estimate as college costs have increased since 2020, and that academic year was marked by disproportionately greater funding to students, families, borrowers, and states from the Higher Education Emergency Relief Fund and CARES Act. The upper-bound estimate that nearly half of Parent PLUS borrowers would hit the $20,000 loan cap is derived from our analysis of U.S. Department of Education data which showed that in AY 2023-2024, Parent PLUS borrowers took out an average of $19,765. See U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, 2023-2024 AY Direct Loan Volume by School (archived link here). Since normally distributed datasets have half of data points above the mean and/or median, we concluded that up to half of Parent PLUS borrowers may take out more than approximately $20,000, as an upper-bound estimate. The “17.1 percent” figure paraphrases the aforementioned Century Foundation research, where the author found the percent of Parent PLUS borrowers who borrowed more than $65,000 in AY 2019-2020 using National Postsecondary Student Aid Study data via NCES Datalab (retrieval code: fmooyz). ↩︎

- The OBBBA’s $65,000 aggregate cap for Parent PLUS borrowers applies per dependent student. Parent PLUS borrowers for students who completed their degree programs in AY 2019-2020, cumulatively took out more than $65,000, and did not have any siblings simultaneously enrolled in college, took out a median balance of $90,264. See National Postsecondary Student Aid Study data via NCES Datalab (retrieval code: cmpfur). We assume they make up the entire shortfall ($25,264) through a private student loan. We calculate the additional interest by assuming the borrower finds a private undergraduate student loan with an interest rate of 10.10 percent, which is the weekly average at the time of writing this analysis, after having lost access to Parent PLUS loans which on average had an interest rate of 7.27 percent from AY 2015-2016 to AY 2025-2026. See Business Insider (archived link here); Education Data Initiative; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid (archived link here). We additionally assume that this is a fixed interest rate, though the aforementioned private rate is variable (which are generally lower than fixed rates). The additional interest is calculated for a principal of $25,264, a repayment period of 10 years, the assumption that the borrower repays the loan in full, and (for simplicity) the assumption that interest does not accrue and the borrower does not have to begin repayment until after their dependent completes their degree. If this last assumption is negated, the total interest paid and the difference between the two loan types would be greater. The borrower would pay $10,359.69 in interest on the Parent PLUS loans, and $14,967.94 in interest on the private undergraduate loans, leading to a difference of $4,608.25. ↩︎

- We assume that the average bachelor’s degree holder owes the average amount of student debt in 2025 Q2 ($37,444.19), repaid at the most recent interest rate of Direct Subsidized and Unsubsidized Undergraduate loans for AY 2025-2026 (6.39 percent) for all years of loan originations, with the repayment term specified for the aforementioned balance amount in the OBBBA (15 years). See U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, Data Center, Federal Student Aid Portfolio Summary; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, Interest Rates (archived link). ↩︎

- We assume that the average master’s degree holder owes the average amount of graduate-only student loan debt for MA/MS holders last reported by NCES in AY 2019-2020 ($53,920), repaid at the interest rate of Direct Unsubsidized Graduate and Professional loans for AY 2025-2026 (7.94 percent) for all years of loan originations, with the repayment term specified for the aforementioned balance amount in the OBBBA (20 years). See NCES, Digest of Education Statistics; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, Interest Rates (archived link). ↩︎

- We assume that the average professional degree holder owes the average amount of graduate-only student loan debt for professional doctoral holders (which includes professional degrees in the fields of chiropractic, dentistry, law, medicine, optometry, pharmacy, podiatry, and veterinary medicine) last reported by NCES in AY 2019-2020 ($169,730), repaid at the interest rate of Direct Unsubsidized Graduate and Professional loans for AY 2025-2026 (7.94 percent) for all years of loan originations, with the repayment term specified for the aforementioned balance amount in the OBBBA (25 years). See NCES, Digest of Education Statistics; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, Interest Rates (archived link). ↩︎

- We assume that the typical bachelor’s degree holder and borrower makes the median income of a bachelor’s degree holder in 2024 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics ($80,236). Under SAVE, they would be eligible for $187.60 monthly payments (totaling $2,251.18 annually). Under RAP, they would be eligible for $534.91 monthly payments (totaling $6,418.88 annually). RAP would force the borrower to pay $347.31 more per month and $4,167.71 more per year. See Bureau of Labor Statistics (archived link). ↩︎

- We assume that the typical borrower with some college and no degree makes the median income of someone with some college and no degree in 2024 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics ($53,040). Under SAVE, they would be eligible for $74.28 monthly payments (totaling $891.38 annually). Under RAP, they would be eligible for $221 monthly payments (totaling $2,652 annually). RAP would force the borrower to pay $146.72 more per month and $1,760.63 more per year. See Bureau of Labor Statistics (archived link). ↩︎

- We assume that the typical bachelor’s degree holder and borrower makes the median income of a bachelor’s degree holder in 2024 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics ($80,236). Assuming that they are the sole earner of their household, and they have a partner and two dependent children, the borrower would be eligible for $32.91 monthly payments (totaling $394.93 annually) under SAVE. Under RAP, they would be eligible for $434.91 monthly payments (totaling $5,218.88 annually). RAP would force the borrower to pay $402 more per month and $4,823.96 more per year. See Bureau of Labor Statistics (archived link). ↩︎

- We assume that the typical borrower with some college and no degree makes the median income of someone with some college and no degree in 2024 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics ($53,040). Assuming that they are the sole earner of their household, and they have a partner and two dependent children, the borrower would be eligible for $0 monthly payments under SAVE. Under RAP, they would be eligible for $121 monthly payments (totaling $1,452 annually). RAP would force the borrower to pay $121 more per month and $1,452 more per year. See Bureau of Labor Statistics (archived link). ↩︎

- We assume that the typical bachelor’s degree holder and borrower makes the median income of a bachelor’s degree holder in 2024 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics ($80,236). Under the post-2014 IBR formula, which applies to loans taken out after 2014, they would be eligible for $473.01 monthly payments (totaling $5,676.10 annually). Under SAVE, they would be eligible for $187.60 monthly payments (totaling $2,251.18 annually). IBR would force the borrower to pay $285.41 more per month and $3,424.93 more per year. See Bureau of Labor Statistics (archived link). ↩︎

- We assume that the typical bachelor’s degree holder and borrower makes the median income of a bachelor’s degree holder in 2024 according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics ($80,236). Assuming that they are the sole earner of their household, and they have a partner and two dependent children, the borrower would be eligible for $32.91 monthly payments (totaling $394.93 annually) under SAVE. Under IBR, they would be eligible for $266.76 monthly payments (totaling $3,201.10 annually). IBR would force the borrower to pay $233.85 more per month and $2,806.18 more per year. See Bureau of Labor Statistics (archived link). ↩︎

- Since a majority of Parent PLUS borrowers are also Pell Grant recipients, and most Pell Grant recipients come from families that make $40,000 annually or less, we conservatively assume that the average Parent PLUS borrower makes $40,000 (while realistically, many earn significantly less than $40,000). See The Century Foundation; National College Attainment Network. We assume the Parent PLUS borrower is the sole earner of their household of four, consisting of two parents, the borrower and their partner, plus the median number of dependent children per family in 2023 according to the U.S. Census Bureau (1.9, rounded up to 2). See U.S. Census Bureau. Under the ICR Plan, the borrower would be eligible for $130.83 monthly payments (totaling $1,570 annually). For calculating payments under the Standard Plan, we assume the borrower has a principal balance of $19,765 (the median amount of Parent PLUS loans originated in AY 2023-2024) and an interest rate of 8.94% (the AY 2025-2026 Parent PLUS rate) that remains the same across all loan origination years. See U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, Data Center (archived link); U.S. Department of Education. Under the new Standard Plan, they would be eligible for $249.74 monthly payments (totaling $2,996.89 annually). The Standard Plan would force the borrower to pay $118.91 more per month and $1,426.89 more per year. ↩︎

- Since a majority of Parent PLUS borrowers are also Pell Grant recipients, and most Pell Grant recipients come from families that make $40,000 annually or less, we conservatively assume that the average Parent PLUS borrower makes $40,000 (while realistically, many earn significantly less than $40,000). See The Century Foundation; National College Attainment Network. We assume the Parent PLUS borrower is the sole earner of their household of four, consisting of two parents, the borrower and their partner, plus the median number of dependent children per family in 2023 according to the U.S. Census Bureau (1.9, rounded up to 2). See U.S. Census Bureau. Under the RAP Plan, the borrower would be eligible for $166.67 monthly payments (totaling $2,000 annually). For calculating payments under the Standard Plan, we assume the borrower has a principal balance of $19,765 (the median amount of Parent PLUS loans originated in AY 2023-2024) and an interest rate of 8.94% (the AY 2025-2026 Parent PLUS rate) that remains the same across all loan origination years. See U.S. Department of Education, Office of Federal Student Aid, Data Center (archived link); U.S. Department of Education. Under the new Standard Plan, they would be eligible for $249.74 monthly payments (totaling $2,996.89 annually). The Standard Plan would force the borrower to pay $83.07 more per month and $996.89 more per year. ↩︎